Audiophile Records – What Are They?

The term “audiophile” has a number of meanings; one definition we found was, “hi-fi enthusiast: somebody who has an enthusiasm for sound reproduction, especially high-fidelity music recordings.” That’s probably a good overall assessment; it’s someone who has an appreciate for how music sounds.

The term “audiophile” has a number of meanings; one definition we found was, “hi-fi enthusiast: somebody who has an enthusiasm for sound reproduction, especially high-fidelity music recordings.” That’s probably a good overall assessment; it’s someone who has an appreciate for how music sounds.

What are audiophile records? Presumably, “audiophile records” would refer to records that were created for the enjoyment of people who like well-recorded sound.

Or, in short, “records that sound good.” In that case, why aren’t all records audiophile records? After all, no one makes records to intentionally sound bad, do they?

No, companies don’t intentionally make records that sound bad, though many records don’t sound as good as they possibly could.

All record companies intend for their product to be enjoyable for the listener. That said, every record company and every artist has different objectives in terms of what they’re trying to accomplish, and who they’re trying to please when they release a record. Is the goal to make money?

To make sure the artist is pleased with the result? Or to give the listener the best possible experience? Sometimes, these objectives are at odds with one another, and the result is often a record that doesn’t sound as good as it could. While all records could be audiophile records, few of them actually are.

Ideally, all recordings would be made under ideal recording conditions, with the greatest care taken to ensure that the recording produced a realistic reproduction of the music played in the studio. The tapes would then be transferred to production stampers with the greatest of care, and the records would be pressed using quiet, high-quality vinyl and packaged in such a way as to protect the finished disc as much as possible.

In a mass-production record company environment, those results rarely occur, though they are becoming more common as the record companies realize that consumers are now more picky than ever before about how they spend their money.

While most record companies today strive to make a quality product, from recording to final pressing, that wasn’t always the case. In the era of stereo records, we had a period where many, if not most, records produced qualified as audiophile records, then a long period where virtually none of them did. Today, as we enjoy the return of vinyl records to the marketplace, fans of well-recorded music are again able to enjoy listening to audiophile records.

Browse by Category

Click any of the links below to jump to each category:

Early Audiophile Records

Audiophile Records by Design

Sheffield Lab

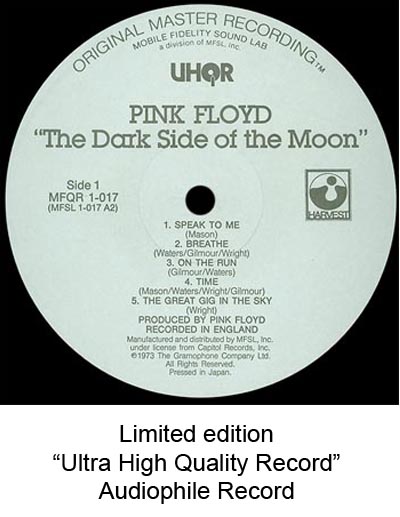

Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs

Other Modern Audiophile Records Labels

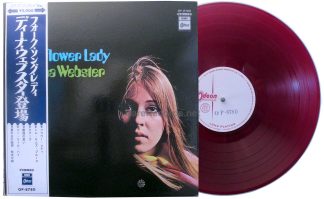

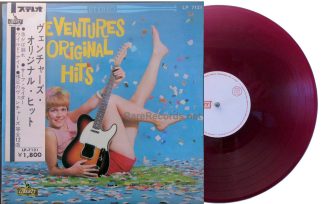

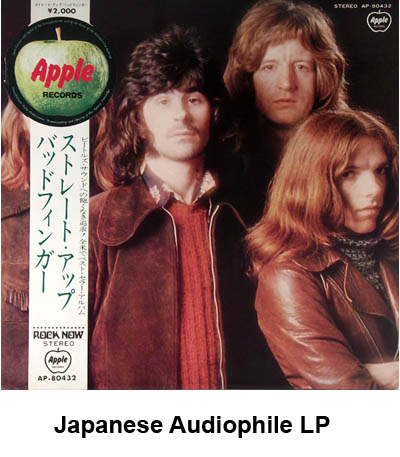

Japanese Audiophile Records

Audiophile Records Today

Featured Products

-

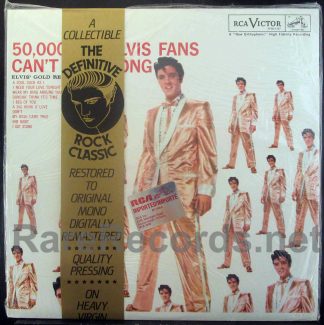

Elvis Presley – Elvis Golden Records Vol 2. 1984 sealed virgin vinyl remastered U.S. mono LP

$60.00Free U.S. shipping! A 1984 still sealed digitally remastered mono U.S. pressing of Elvis' Golden Records Vol. 2 by Elvis Presley.Add to cart -

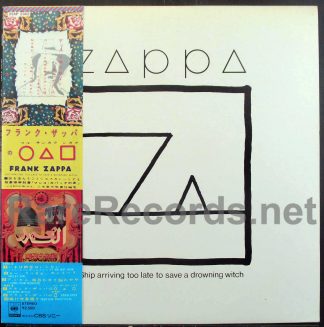

Frank Zappa – Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch Japan LP with obi

$99.00Free U.S. shipping! An original Japanese pressing of the 1982 LP Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch by Frank Zappa, including the original obi.Add to cart -

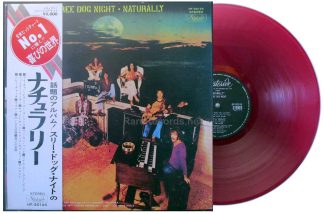

Three Dog Night – Naturally 1970 red vinyl Japan LP with obi

$150.00Free U.S. shipping! An original Japanese red vinyl pressing of Naturally, the fourth album by Three Dog Night, including the original obi.Add to cart

Click here to browse our selection of audiophile records.

Early Audiophile Records

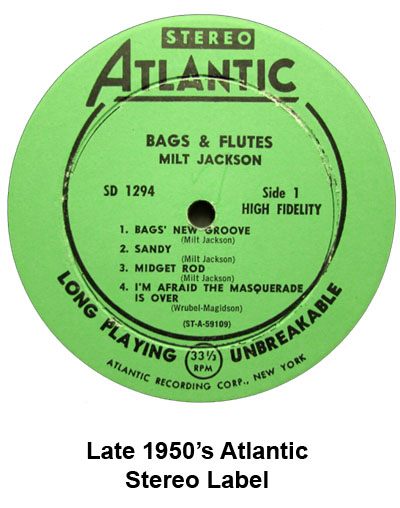

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few record companies, such as Columbia and Atlantic, spent a lot of time trying to make sure that their recordings sounded great and that their finished product was of a high quality. Their albums were well-recorded, with a sense of space and depth that truly immersed the listener in the experience.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few record companies, such as Columbia and Atlantic, spent a lot of time trying to make sure that their recordings sounded great and that their finished product was of a high quality. Their albums were well-recorded, with a sense of space and depth that truly immersed the listener in the experience.

Both companies were early adopters in acquiring then-expensive stereo and/or multi-track tape recording equipment. In addition, their records were pressed from quality vinyl, with quiet surfaces that reproduced the music well without producing distracting noise or ticks or pops that often comes with records pressed from poor quality or recycled vinyl compounds.

In the late 1950s, those companies, along with RCA, discovered that those consumers who were early adopters in buying stereo playback equipment had larger than average amounts of disposable income and they set out to make a quality product to appeal to those buyers. That’s not surprising; the cost of a stereo record album in 1960 equates to more than $40 today. Buying a new record back then was not an impulse purchase.

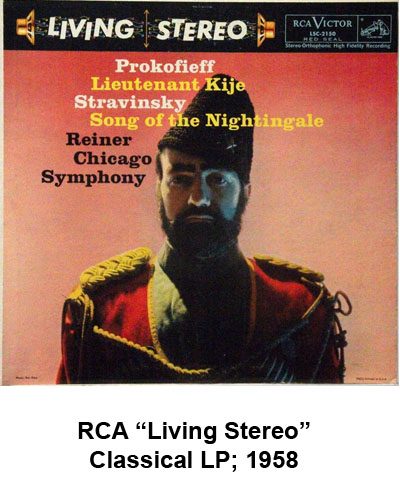

RCA in particular was an innovator in stereo recording, particularly in their classical releases, which were recorded using a three track tape recorder to capture the left, right, and center of the orchestra. These techniques were later used for RCA’s popular recordings, as well, and their records, issued under the “Living Stereo” banner, captured a realism that is still revered by audiophiles today. Many RCA stereo albums from that era command prices in the hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of dollars on the collector market.

This early “golden age” of stereo and high quality recordings didn’t last all that long; in fact, it was over in less than a decade. There were various reasons for changes in the industry, but the result was the mass production of records that, for the most part, didn’t sound that great when compared to what had been available just a few years before.

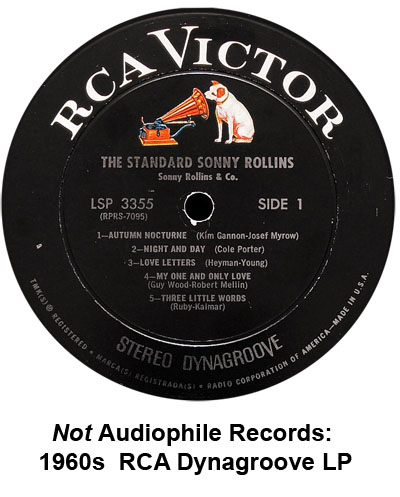

The price of stereo equipment began to drop as the 1960s wore on, and more people started buying stereo records. Their lower-priced equipment didn’t do as good a job of reproducing stereo sound, and RCA compensated for this beginning in 1963 when they introduced their “Dynagroove” process.

The price of stereo equipment began to drop as the 1960s wore on, and more people started buying stereo records. Their lower-priced equipment didn’t do as good a job of reproducing stereo sound, and RCA compensated for this beginning in 1963 when they introduced their “Dynagroove” process.

Dynagroove attempted to compensate for the deficiencies of consumer-grade equipment by artificially boosting bass frequencies and reducing the overall volume level of the music on the records.

While RCA claimed that the Dyangroove process added “a remarkable degree of musical realism,” the music community disagreed as did many stereo and hi-fi publications of the time.

Unfortunately, RCA continued using this process for all of their recordings for nearly a decade. By the time they stopped using it, they’d already adopted something far worse – Dynaflex, which we’ll cover shortly.

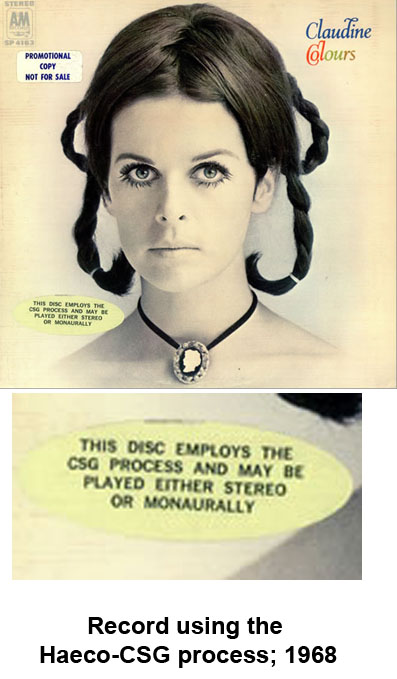

Another mid-1960s process that hurt the sound of records was the Haeco-CSG process, which attempted to correct a problem caused when consumers played stereo records on mono phonographs.

Between 1957, when stereo records were first introduced and sold alongside their mono counterparts, and 1968, when mono records were finally phased out, consumers had to choose either mono or stereo records when they made a purchase. Early mono phonographs could not play stereo records without damaging them, but by the late 1960s, manufacturers were using needles that were compatible with both formats.

The problem during playback was that a stereo record played on mono equipment would artificially boost the sound of any information that was present in both channels of the stereo disc. This resulted in recordings that didn’t sound right, as part of the music, usually the vocals, would play back at a higher sound level than intended.

The Haeco-CSG (“compatible stereo groove”) process attempted to correct this and allowed record companies to produce a record in one format only – stereo, which would play back at the same level regardless of the type of phonograph used to play it.

While this was great for record companies, as it allowed them to dramatically reduce manufacturing costs, it was terrible for consumers who appreciated high-quality sound, as the phase-cancellation process used by CSG resulted in “tinny” sounding records with relatively little bass.

While this was great for record companies, as it allowed them to dramatically reduce manufacturing costs, it was terrible for consumers who appreciated high-quality sound, as the phase-cancellation process used by CSG resulted in “tinny” sounding records with relatively little bass.

Although the CSG process was used for only two or three years, it was often used at the master tape mixing stage, leaving master tapes of albums released during this time by several major record companies (the Warner-Elektra-Atlantic group among them) forever sounding artificially wrong.

While there are now processes available to remove the CSG artifacts from recordings from the 1968-1970 era when it was primarily used, most copies of albums released during that era suffer from poor sound quality due to its use.

By the early 1970s, various record company mergers with other labels and acquisitions by companies with no prior interest in music (such as Kinney’s buyout of Warner Brothers in the late 1960s – Kinney’s primary business to that point was managing parking garages and janitorial services) led to an increased interest in the bottom line and an emphasis on producing greater profits over producing a good-sounding, quality product.

These mergers, combined with a global oil crisis and a relative shortage of vinyl, led to cutbacks in quality across the industry. Many records were lighter in weight and indifferently manufactured, resulting in records with lots of surface noise and a tendency to warp. Making matters worse was the tendency of the record companies to press their records from noisy, recycled vinyl. With new vinyl (and the oil needed to make it) being scarce, companies would grind down their unsold product and reuse it for new releases.

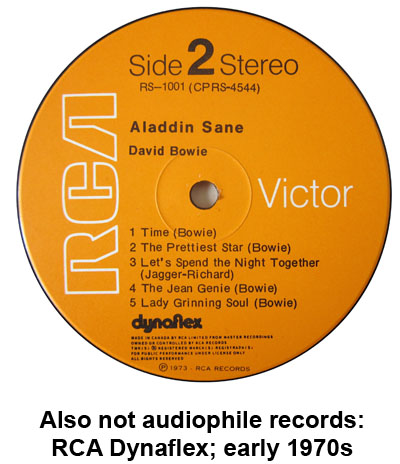

Perhaps the worst example of this were the records RCA pressed at this time. These were extraordinarily thin pressings were so thin that you could almost fold them in half.

Perhaps the worst example of this were the records RCA pressed at this time. These were extraordinarily thin pressings were so thin that you could almost fold them in half.

RCA knew these records were of poor quality, but they attempted to sell this obvious step back in quality as a feature, which they even chose to name – Dynaflex. These records were quite flexible, and weighed about half as much as a regular LP.

Dynaflex records sounded terrible and were prone to warping, but RCA actually advertised these pressings as an improvement, going so far as to claim that they were less likely to warp than traditional pressings from heavier vinyl.

While Dynaflex records were less prone to actual breakage than their predecessors, they were more prone to warpage, leading to the derisive nickname, “Dynawarp.” If you were unfortunate enough to buy albums from RCA artists around 1970 or so, you had the double problem of purchasing records by likes of the Guess Who, Elvis Presley or Jose Feliciano that were plagued by the problems of both Dynagroove and Dynaflex. You spent the same money that you used to, but now you received a product with thin, compressed sound on a disc that was more likely then ever to warp.

Adjusted for inflation, records were far more affordable in the early 1970s than they had been a decade earlier. This led to increased sales. Record companies expanded and opened more pressing plants, but this led to yet another decrease in quality. Ideally, to get the best-sounding record, you want to use the two-track master tape to make it.

This isn’t possible, of course, as record companies don’t want to use their only two track master to produce millions of records. The tape would wear out if they did that. So they’d use copies of that tape instead. Sometimes, they’d use copies of copies, with each copy sounding worse than the tape from which it was made. The product was widely available at an affordable price, but the finished product sounded worse than ever.

As a side note, there was a small label in operation from the late 1940s through the 1970s that called itself “Audiophile Records.” This label specialized in jazz recordings, and took great care in making sure their records sounded as good as possible.

As a side note, there was a small label in operation from the late 1940s through the 1970s that called itself “Audiophile Records.” This label specialized in jazz recordings, and took great care in making sure their records sounded as good as possible.

As far as we know, all of their releases were pressed on red vinyl, and many of their early titles were cut at 78 RPM, as the company felt that speed offered better fidelity. Despite the label’s attention to quality, they were never overly successful, with their records being seen as a niche market.

The 1960s and early 1970s were not a good time for audiophiles, as the mass-produced product of that decade largely resulted in poor quality pressings made from noisy vinyl. It didn’t matter if the albums were well-recorded or not, as they playback was likely to sound terrible regardless of what kind of equipment you were using to listen to it.

In the early 1970s, a record mastering engineer named Doug Sax and a musician named Lincoln Mayorga discovered that many of their old 78 RPM singles sounded better than newer recordings. This led to the formation of one of the earliest companies to intentionally produce audiophile records – Sheffield Lab.

In the early 1970s, a record mastering engineer named Doug Sax and a musician named Lincoln Mayorga discovered that many of their old 78 RPM singles sounded better than newer recordings. This led to the formation of one of the earliest companies to intentionally produce audiophile records – Sheffield Lab.

Sheffield specialized in “direct-to-disc” recordings, which sent the signals from the artists’ microphones directly to the cutting lathe, bypassing the tape deck (though a tape deck was used as a backup.) These recordings produced records of astonishing depth and clarity and the label’s occasional releases became quite popular in the hi-fi and audiophile community.

There are several problems with the direct-to-disc process, however. Because the music is recorded live to the acetate, an entire album side had to be played and recorded at once, with no opportunity to make corrections later or overdub instruments or additional voices at a later time.

What was played live was what went on the record. Another problem was that the lack of a master tape meant that when the stampers wore out, production of a particular title must come to a stop forever.

Since most artists were, by that time, accustomed to recording in a studio with 8, 16 or even 32 track tape recorders and were more comfortable with a recording process that allowed them to record, and overdub or make corrections at leisure, direct-to-disc recordings were somewhat of a niche product that worked best with small jazz groups, who were accustomed to performing live with limited overdubbing.

A few other labels attempted to produce records using similar direct-to-disc methods, including Century, Direct Disk Labs, Crystal Clear and M&K Realtime, but most of them were out of business by the early 1980s.

Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs Audiophile Records

In the late 1970s, a company called Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, founded by Brad Miller, decided that it was time to produce audiophile records, meaning records that manufactured to sound good as the music on them, and records intended for people who actually care how their music sounds.

In the late 1970s, a company called Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, founded by Brad Miller, decided that it was time to produce audiophile records, meaning records that manufactured to sound good as the music on them, and records intended for people who actually care how their music sounds.

Mobile Fidelity wasn’t new; the company had been founded around 1960 as an outlet for recordings of locomotives for train buffs. The company later expanded to include a few race car recordings, but through the 1960s, they were mostly a company that produced high-quality, but little-noticed, sound effects records.

In the mid-1970s, the owners of the label had noticed that the records issued by the major labels were of relatively poor quality and that they sounded a lot worse than what had been available ten or fifteen years earlier.

They came up with what was then a novel idea to produce higher-quality records than what was then available, allowing listeners to experience well-recorded albums, such as Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon or John Klemmer’s Touch, as they were meant to be heard.

Miller’s plan was to approach the major labels and license recordings to some of their albums from major artists. They would negotiate, for example, with Capitol Records to release Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon themselves. They would insist on using only the master two-track tape, rather than a copy, or a copy of a copy.

The acetate from which the stampers were made was cut on the lathe using a process known as half speed mastering. Half speed mastering was a process where both the tape recorder playing back the album during mastering and the cutting lathe that cut the acetate from which stampers were made were both run at half of the normal speed, thus creating a more accurate groove in the record. This process, which required special equipment and a lot of extra time, was also thought to improve spatial imaging and bass response in the finished product.

The company also made the decision to use only new, high-quality, “virgin” vinyl, as opposed to the recycled vinyl that was then in use by nearly every major record company.

The company also made the decision to use only new, high-quality, “virgin” vinyl, as opposed to the recycled vinyl that was then in use by nearly every major record company.

The vinyl that Mobile Fidelity used was a proprietary compound made by JVC in Japan called Supervinyl and had JVC manufacture the records in Japan. It was translucent, with a brownish-gray color when held to the light, had exceptional wear properties for repeated play, and had dead-quiet surfaces that allowed you to hear just the music, rather than a combination of music and record surface noise.

Mobile Fidelity sold their records for nearly double the price of that of the major record companies, but enjoyed considerable success in the days prior to the invention of the compact disc. Their records were available in specialty record shops and at hi-fi stores, which often used their albums as demonstration discs.

Mobile Fidelity also declared up front that all of their titles were to be limited editions, claiming that fewer than 200,000 copies of any of their titles would ever be pressed. While this appeared to be an appeal to scarcity to encourage sales, it actually had more to do with requirements from the record companies from whom they were licensing the recordings. Most, if not all, of their contracts had time limitations on them; Mobile Fidelity could only sell a particular title for a specified period of time before they were contractually required to discontinue their sales of that title.

By licensing titles that were already big sellers, such as the Pink Floyd LP, Supertramp’s Crime of the Century, and the Grateful Dead’s American Beauty, Mobile Fidelity became quite successful, though not all record companies were interested in licensing their product to the label, nor were they interested in having it demonstrated to the public that the records they were selling themselves didn’t sound very good.

In 1982, Mobile Fidelity went a step further in producing audiophile records by creating the Ultra High Quality Record, or UHQR. These records used heavier, 200 gram vinyl, than the regular 140 gram releases from the company. The records were truly flat, unlike regular records, which tended to be thicker in the middle than at the edge. The records were kept in the presses longer than their regular releases in order to produce a better-defined disc. Only eight of these UHQR releases were ever issued, and they were limited to 5000 copies per title and were sold at a then-outrageous retail price of $50.

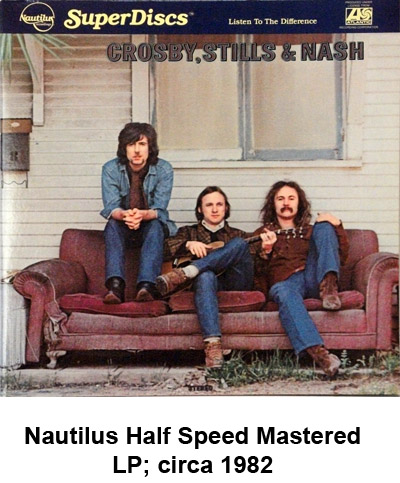

Other Modern Audiophile Records Labels

With the success of Mobile Fidelity, other companies soon joined the trend of releasing mass-produced audiophile records. Some of the early competitors were California-based Nautilus and Nashville’s Direct Disk Labs.

With the success of Mobile Fidelity, other companies soon joined the trend of releasing mass-produced audiophile records. Some of the early competitors were California-based Nautilus and Nashville’s Direct Disk Labs.

Nautilus produced about 50 titles through the early 1980s, before going out of business due to financial issues with their owner. They did, however, produce noteworthy titles by The Allman Brothers Band, Elton John, and John Lennon, among others.

Direct Disk Labs had best been known for their direct-to-disc releases, but they ventured into the same territory as Mobile Fidelity and Nautilus by licensing titles by Derek & the Dominoes, Elton John and Peter Gabriel, among others.

They only issued a handful of titles, but were noteworthy in that they released titles by artists who recorded for Columbia Records, a label whose products Mobile Fidelity didn’t release. Those titles included albums by Neil Diamond, Blood Sweat & Tears, and Loggins & Messina.

As they were then the largest record company, Columbia Records didn’t see that it made sense to license their titles to other companies who would then try to sell them by suggesting that their products were better than what Columbia was producing, even though that was exactly the case.

So in 1981, Columbia Records decided to make their own audiophile records, releasing both half speed mastered pressings of titles recorded on analog tape and albums using the then-new digital recording process, though the digital titles were mostly classical. These pressings were made entirely in-house, and used a higher quality vinyl than what Columbia used for their regular pressings.

Columbia’s audiophile records consisted of an odd mix of older, classic titles combined with then-new releases.

Columbia’s audiophile records consisted of an odd mix of older, classic titles combined with then-new releases.

While Columbia’s titles, which included albums by Bob Dylan, Boston, Pink Floyd, Barbra Streisand, Willie Nelson, Earth Wind & Fire and others were quite good, many buyers and audiophiles were annoyed by the combination of prices that were double those of Columbia’s regular pressings and by the fact Columbia was effectively choosing to improve a small selection of their products, when they had the ability to improve the quality of their entire product line.

Instead, the more expensive, higher quality audiophile records sat in the same bins as the noisy, indifferently manufactured regular pressings, with both produced by the same company.

In Canada, A&M records started their own line of half speed mastered audiophile records, and had them pressed by JVC in Japan using their proprietary “Super Vinyl.” Many of these titles, by artists such as Supertramp, Styx, the Carpenters, and The Police, were widely available for sale in the United States.

While these records looked a lot like those from Mobile Fidelity and used a similar half speed mastering process, the tapes used to make these audiophile records were at least one generation down in the duplication chain from those used to produce Mobile Fidelity records, resulting in a product with a quiet playing surface but sometimes spotty sound.

With the increased number of companies producing audiophile records, consumers were confused and frustrated by the experience of seeing the same titles sometimes offered in multiple versions at a wide variety of price ranges with little information offered as to what, exactly, they were buying. By the mid-1980s, a glut in the market and the introduction of the compact disc put all of these companies except Mobile Fidelity out of business.

While all of this was going on, a few people quietly noticed that records imported from Japan tended to always sound better than their American counterparts.

While all of this was going on, a few people quietly noticed that records imported from Japan tended to always sound better than their American counterparts.

Part of that had to do with the fact that the Japanese record companies always used premium materials in their product manufacturing – the vinyl was of high quality, their cover printing was of high quality and they took great care in the mastering of their acetates and plating of their stampers.

The Japanese record companies even packaged their records using non-abrasive rice paper inner sleeves, instead of the heavy paper used by American record companies that often damaged the discs after repeated play.

In the early 1980s, tens of thousands of Japanese LPs were imported into the United States and sold as high quality “audiophile records.” Many of these titles were pressed in Japan by JVC, the same company that was pressing records for Mobile Fidelity, often using the same vinyl, though rarely the same master tapes.

The importation of Japanese audiophile records was halted in the mid-1980s when the American record companies realized that they were losing money on sales of imported records. Royalty payments to artists are negotiated on a country-by-country basis, with higher rates in the United States and Great Britain than in other countries, such as Japan.

If an American buyer purchased an imported Japanese album of a title that was also available as a domestic pressing, the royalty payment to the artist and likely the profit to the record company itself, would be less.

With the record companies putting an end to the importation of Japanese audiophile records, they then set out to try to get rid of the record altogether, instead promoting the digital compact disc, which had significantly higher profit margins. Unfortunately, audiophiles didn’t care for the sound of compact discs, and many simply stopped buying music altogether as records became scarce in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Audiophile Records Today

After forcing records from the market in the early 1990s, the record companies found themselves with little product to sell after consumers balked at paying high prices for compact discs and resorted instead to illegally downloading low-quality mp3 files from the Internet.

After forcing records from the market in the early 1990s, the record companies found themselves with little product to sell after consumers balked at paying high prices for compact discs and resorted instead to illegally downloading low-quality mp3 files from the Internet.

Realizing that they could still sell physical product if they made something that people felt was worth buying, the major record labels started selling a high-quality product that has long been popular with the public – records.

The public has responded, and today, every pressing plant in the world is running at full capacity.

Today, with the resurgence in sales of vinyl, lots of companies are again making audiophile records. After a brief period of bankruptcy, Mobile Fidelity is back in business, and Warner Brothers Records is selling albums on a Website with the title Because Sound Matters.

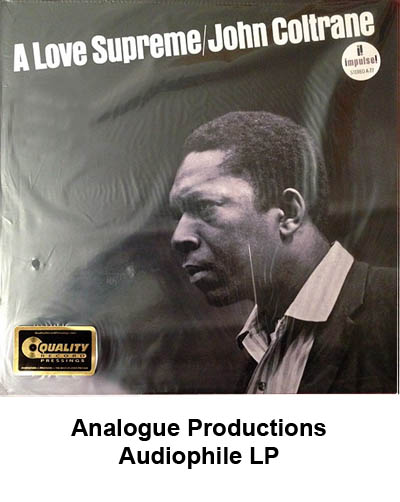

Often, these are limited edition pressings cut at 45 RPM (on twice as many discs) to produce even better sound quality than the standard 33 1/3 pressings. Mobile Fidelity is back in business again after a short period of bankruptcy, and other companies such as Classic Records and Acoustic Sounds have stepped in to add to the quality pressings available on the market. Newer labels include names such as Equinox, Analogue Productions and the Electric Recording Company.

The latter company produces painstakingly detailed reproductions of obscure classical titles that are limited to 300 copies only. The titles they choose to release may be obscure, but they’re albums that often sell for upwards of $1000 on the collector market.

Analogue Productions has been producing audiophile records in two versions – a regular pressing that plays at 33 1/3 RPM and a pressing that plays at 45 RPM. The 45 RPM pressings require that a single album be spread over two discs, but the higher speed allows for less distortion and better sound quality. The company is doing so well that they have built their own pressing plant.

Across the board, the overall quality of the records available today is the best it’s ever been. Record companies today are making a determined effort to make their product as good as possible, with careful attention paid to the quality of the mastering process, the quality of the vinyl used in pressing the records themselves and the tapes used in the mastering process.

While sales of vinyl records are the highest they’ve been in twenty five years, the sale of records is still a niche industry, as most consumers purchase digital downloads. As records represent a premium product that sells at a premium price, the companies making records today realize that quality matters more than ever, and if they don’t make a good product, consumers are going to take their business elsewhere.

The term “audiophile records” is really rather vague, and can encompass a wide variety of recordings, both those intended to be of high quality, such as those from Mobile Fidelity, as well as vintage titles that sounded great because that’s how the record companies at that time made all of their products. Nevertheless, if there’s a record out there that sounds great, with a wide soundstage and a sense of three dimensional depth to it, you can rest assured that people will be lining up to buy it.

Records today sound better than ever. If you like quiet vinyl and good representation of the recorded music on it, you may find audiophile records to be to your liking.

Click here to browse our selection of audiophile records.

Share this:

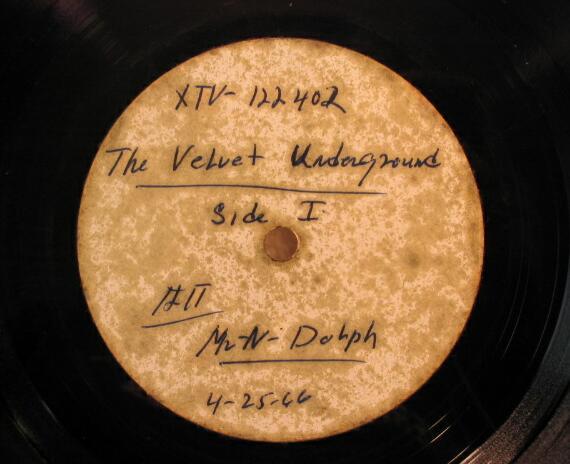

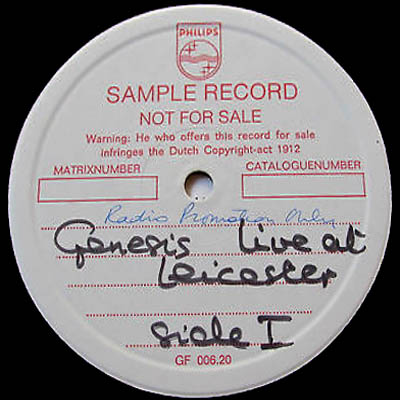

Example of an acetate label[/caption]

Example of an acetate label[/caption]