Stereo Records vs. Mono Records

If you’re a record collector and you collect albums made between 1957 and 1970 or so, you’re likely to encounter something that compact disc buyers have never had to deal with – copies of an album pressed in either mono or stereo. For roughly a decade, people who purchased record albums in stores had to make a choice – do you buy the mono or the stereo copy?

If you’re a record collector and you collect albums made between 1957 and 1970 or so, you’re likely to encounter something that compact disc buyers have never had to deal with – copies of an album pressed in either mono or stereo. For roughly a decade, people who purchased record albums in stores had to make a choice – do you buy the mono or the stereo copy?

Which one you purchased was largely dependent on what kind of equipment you were going to use to play it. If you had a “record player”, you’d likely buy the album in mono. If you had a stereo system or “hi-fi,”, you’d likely buy a stereo copy.

Today, of course, nearly all newly recorded albums are in stereo, and they’ve been that way for more than fifty years. For collectors, however, the mono vs. stereo issue remains relevant, as many popular artists of the late 1950s and the 1960s released albums in both formats. Which ones should you buy as a collector? Is one format preferable over the other? If so, why?

In this article, we’ll cover the history of mono and stereo records, and explain why both formats exist, why both formats were necessary and why, as a collector, you might have at least a passing interesting in owning one or more albums in the form of both mono and stereo records.

Browse by Category

Click any of the links below to jump to each category:

Mono records

Introduction of stereo records

Incompatibility issues

“Fake” stereo records

Phaseout of mono records

Promotional-only mono records

Why collectors like mono records

Why collectors like stereo records

Conclusion

Click here to browse our selection of mono records.

Click here to browse our selection of stereo records.

Mono Records

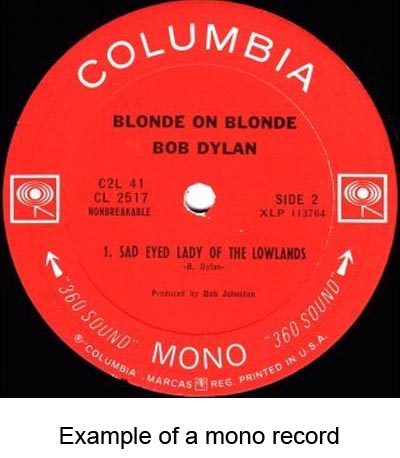

For roughly the first decade that 33 1/3 RPM record albums existed, they all played in monaural, or as they’re commonly known, “mono.” There was one channel of information encoded on the disc, usually sourced from magnetic tape that also had one channel of information.

For roughly the first decade that 33 1/3 RPM record albums existed, they all played in monaural, or as they’re commonly known, “mono.” There was one channel of information encoded on the disc, usually sourced from magnetic tape that also had one channel of information.

During recording, multiple microphones may have been used, but the signals from each microphone would be mixed into a single signal. Record players, even expensive ones, had a single speaker and that was sufficient to provide playback.

This format existed from the introduction of the long-play, or “LP” record in 1948 through the introduction of stereo records in 1957. As all records were pressed in mono, there were no choices to make for buyers – you went to the store and if you saw an album you liked, you bought it, took it home and played it.

That soon changed, and for the next decade, buyers encountered a number of complications when it came to buying record albums at the store.

Introduction of Stereo Records

Experiments in stereo recording and playback date to at least the 1930s, and the soundtrack to the 1940 Disney film Fantasia was recorded in stereo and played back in that format in theaters in some cities. Getting stereo sound in a home format proved a bit more difficult, however.

Experiments in stereo recording and playback date to at least the 1930s, and the soundtrack to the 1940 Disney film Fantasia was recorded in stereo and played back in that format in theaters in some cities. Getting stereo sound in a home format proved a bit more difficult, however.

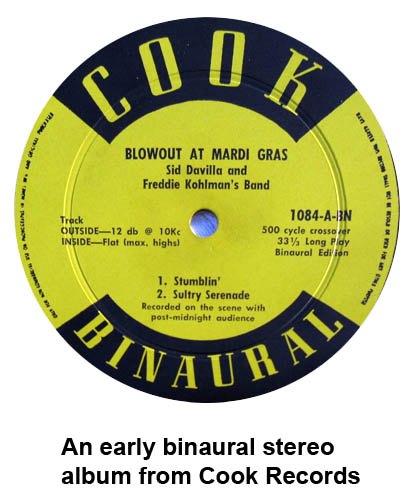

In 1952, an engineer named Emory Cook introduced what he called “binaural recordings,” which were albums that appeared to have two songs on each side. In truth, there was only one, as Cook’s binaural system made use of a tonearm with two cartridges and needles mounted on it that were carefully spaced to correspond to the distance between the beginning of each track on the album.

You can see a demonstration of a turntable playing one of these binaural stereo records here:

There were a few experiments with stereo recordings; Atlantic Records released an album by Wilbur DeParis in 1953 that was recorded in stereo and released as a “binaural disc.” This record required a special player that used a tonearm with two needles. Cook also offered an adapter, which he sold for $5.95 (about $60 today) that could convert a standard tonearm into one capable of playing binaural records.

Cook formed his own record company, Cook Records, which released about 50 titles in the binaural format. Atlantic Records released one title in the format by Wilbur DeParis and a few other small record companies released a few titles as binaural recordings. The format was a bit awkward, and the fact that each channel required its own track also limited the playing time for these records. Due to these inconveniences, the binaural system never really caught on.

In December 1957, Audio Fidelity released what is generally regarded as the first stereo record album – a recording of the Dukes of Dixieland on one side and railroad recordings on the other. This release attracted a lot of attention from the audiophile community, and other labels slowly entered the stereo market.

The decision to embrace stereo records was a difficult one for both record labels and consumers. For the record companies, it meant buying then-expensive stereo tape recorders in order to record their music in stereo. It also meant buying new mastering equipment or modifying existing cutting lathes to cut stereo discs. There was a learning curve for both recording and mastering engineers, who needed to figure out how to accurately produce stereo sound on vinyl.

For consumers, the issue was also about expense. Anyone who wanted to listen to music in stereo would have to replace their phonograph or turntable. They would also have to either buy a second mono amplifier or replace their mono amplifier with a stereo model. They would also have to buy a second speaker. Buying what was essentially a second hi-fi system in order to play stereo records was a non-trivial expense, and for the first few years that stereo records were available, they sold in tiny amounts compared to mono pressings.

For consumers, the issue was also about expense. Anyone who wanted to listen to music in stereo would have to replace their phonograph or turntable. They would also have to either buy a second mono amplifier or replace their mono amplifier with a stereo model. They would also have to buy a second speaker. Buying what was essentially a second hi-fi system in order to play stereo records was a non-trivial expense, and for the first few years that stereo records were available, they sold in tiny amounts compared to mono pressings.

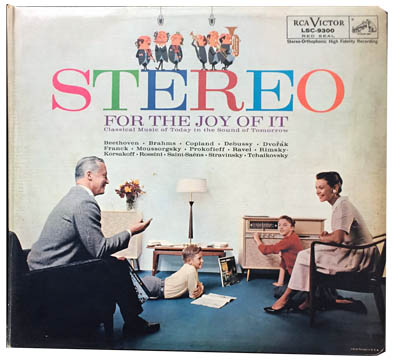

Record companies also needed to educate buyers about the advantages of stereo records. This led many labels to release “stereo demonstration records.” These were usually albums that featured all manner of sounds – vocals, orchestras, locomotives, jet airplanes, and more, all recorded with deep, spacious stereo sound.

Incompatibility Issues Between Mono and Stereo Records

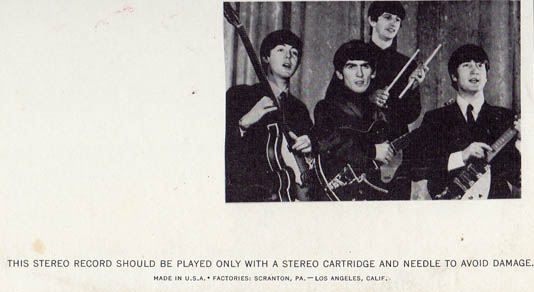

A huge headache for both manufacturers and buyers of record albums was the fact that there were incompatibility issues between mono and stereo records. Most players with mono cartridges had larger, less flexible needles that had a tendency to damage stereo records. Several record companies printed warnings on the covers of their stereo albums that said something like “this record should be played only on stereo equipment to avoid damage.”

Some records noted that stereo records could be played on mono players, provided that the consumer were to replace their cartridge with a stereo cartridge that was wired for mono. This presented another problem – stereo records played on mono players did not reproduce sound properly. Stereo records are mixed to give the sound a three-dimensional sense of space, but most recordings have at least some information, often vocals, that is present in both channels. When stereo records were played back in mono, any information that was present in both channels was amplified by 6 DB, making it louder than than it was intended to be and giving the record an unnatural sound, with vocals and drums sounding louder than intended.

Some records noted that stereo records could be played on mono players, provided that the consumer were to replace their cartridge with a stereo cartridge that was wired for mono. This presented another problem – stereo records played on mono players did not reproduce sound properly. Stereo records are mixed to give the sound a three-dimensional sense of space, but most recordings have at least some information, often vocals, that is present in both channels. When stereo records were played back in mono, any information that was present in both channels was amplified by 6 DB, making it louder than than it was intended to be and giving the record an unnatural sound, with vocals and drums sounding louder than intended.

For manufacturers, these problems meant that for many titles, they’d need to produce two different versions of the album – one on mono and one in stereo. This doubled the workload of the mastering engineers and employees at the pressing plants, who were basically making the same product twice.

Buyers then had to decide when they visited the store which version of a record they wanted to buy. While most mono players couldn’t play stereo records, stereo turntables could play mono records just fine. For buyers, it became a matter of making a decision as to which record they wanted to buy when they chose a particular album – the mono copy or the stereo copy? That, of course, assumed that both mono and stereo versions were available and in stock at the store, and that the record company had chosen to release that particular album in both formats.

A few companies went ahead and labeled their records as being compatible for both stereo and mono players, even though they weren’t. One such company called their records “Stereomonic.”

For the first few years after the introduction of stereo records, record companies were a bit skittish about releasing albums in stereo, due to the added expense and the fact that the stereo pressings were unlikely to sell in large quantities. Because of this, most companies that did venture into stereo in the 1950s only did so in the “adult” markets – jazz and classical. For popular vocal music and the up-and-coming rock and roll, many titles continued to be released only in mono, and stereo rock and roll recordings from that decade are few and far between.

For the first few years after the introduction of stereo records, record companies were a bit skittish about releasing albums in stereo, due to the added expense and the fact that the stereo pressings were unlikely to sell in large quantities. Because of this, most companies that did venture into stereo in the 1950s only did so in the “adult” markets – jazz and classical. For popular vocal music and the up-and-coming rock and roll, many titles continued to be released only in mono, and stereo rock and roll recordings from that decade are few and far between.

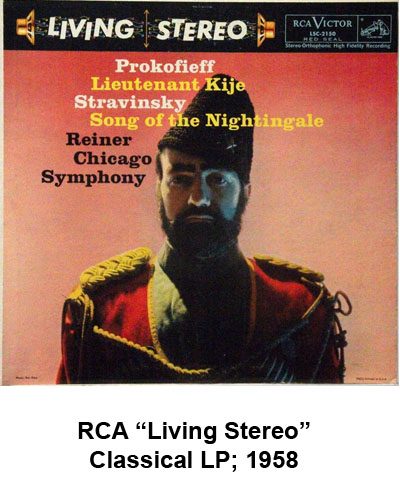

Classical, opera, and jazz fans, however, were often able to buy albums in either mono or stereo, and the record companies were all too happy to have these albums available to show off their ability to record in stereo. To this day, a number of classical recordings from the late 1950s and early 1960s are used as demonstration records, as they were recorded to either two or three channel tape recorders with a minimum number of microphones, producing an ultra-realistic, “you are there” listening experience.

As stereo records were largely a niche product when first introduced, the record companies added a one dollar surcharge to the retail price, making the already-expensive record album even more so. Atlantic Records charged $5.98 for stereo albums in 1960; a price that equates to more than $50 today. Not surprisingly, the high price of stereo records did not encourage more consumers to buy the equipment to play them. Most record companies continued to charge $1 more for stereo records right up until they stopped making mono records in the U.S. in late 1968.

Yet another problem popped up in the early 1960s once stereo records became widely available – a few, but not an insignificant number, of buyers refused to purchase anything other than stereo records. If the album wasn’t available in stereo, these people wouldn’t buy it. While it was nice to have buyers who wanted the more expensive, but also more prestigious, product, most record companies didn’t have that many titles available for purchase in stereo.

Record companies make their money by selling both new releases and titles that have been available, known as “back catalog.” The problem in the early 1960s for stereo buyers was that much of their back catalog wasn’t available in stereo, nor could it be, as nearly all recordings made prior to the introduction of stereo records in 1957 were recorded in mono, making it impossible to release stereo versions of older albums.

A few labels, such as Atlantic and RCA, had seen the stereo revolution coming and had purchased stereo recording equipment in the early 1950s. They had recorded a number of albums in stereo early in the decade, even though the technology of the time did not allow them to release the finished recording in the form of stereo records. For those companies, accommodating the “stereo-only” buyers was a simple matter of pulling the stereo tapes out of the vault and making stereo versions.

In Atlantic’s case, they had stereo tapes in their vault going back to 1952, and in 1958, they made a number of older recordings available in stereo. In 1960, RCA released a number of classical titles that they had recorded as early as 1954.

That was great for those companies that were forward-thinking regarding stereo records. But what about the other companies that hadn’t done that? What about those recordings for which there simply were no stereo tapes?

That was great for those companies that were forward-thinking regarding stereo records. But what about the other companies that hadn’t done that? What about those recordings for which there simply were no stereo tapes?

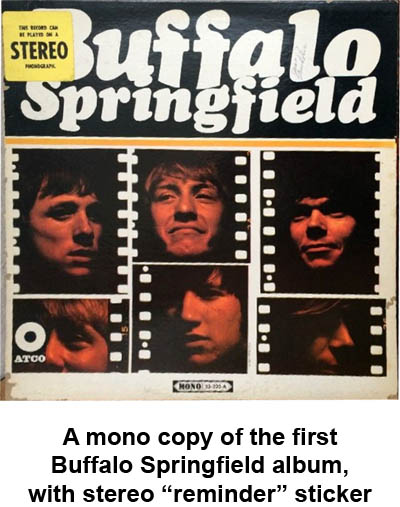

There were several solutions to that. The simplest was to place a sticker on mono records “reminding” prospective buyers that the albums were playable on stereo equipment.

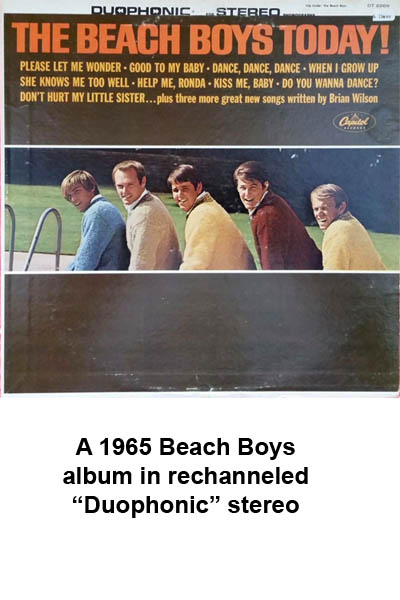

A somewhat more complicated solution was the introduction of what is commonly known as “electronically rechanneled stereo,” “Duophonic,” or more often, “fake stereo.”

The process of creating “stereo” records from mono recordings differed from one record company to another, but most of the time, the companies took a mono tape and split it into two signals. They then used filters to cut high frequencies slightly in one channel while cutting low frequencies slightly in the other. A slight, and almost-imperceptible delay was added to one channel to give an artificial sense of space. Sometimes, echo or reverberation would be added to the recording. Capitol and RCA used the reverb trick quite often, and it’s particularly noticeable on early recordings by Elvis Presley, which were sold exclusively in fake stereo from 1968 through the late 1980s after mono records were phased out.

Even though these recordings weren’t true stereo, they were packaged as stereo records, often with a small note on the cover indicating that the music had been artificially enhanced to simulate stereo. Capitol Records called their fake stereo process “Duophonic” and put a large banner at the top of their records that included the phrase “for stereo phonographs only.” It wasn’t stereo, but the same rules applied as they would to records that were stereo– if you didn’t play it on a stereo player, you’d be likely to damage it.

The introduction of rechanneled stereo helped accommodate those buyers who weren’t interested in buying mono records anymore and also gave would-be buyers of stereo playback equipment the impression that there were more stereo records available for purchase than there actually were.

The introduction of rechanneled stereo helped accommodate those buyers who weren’t interested in buying mono records anymore and also gave would-be buyers of stereo playback equipment the impression that there were more stereo records available for purchase than there actually were.

For most of the 1960s, “stereo” albums might have fallen into one of three categories – “true” stereo recordings, where every album was recorded in stereo, “partial” stereo recordings, where some songs were true stereo and other songs were electronically rechanneled, and “fake” stereo recordings, where every song was in simulated stereo.

This was problematic for buyers, as few stereo records were prominently labeled regarding the actual nature of the content on the disc.

Not all record companies chose to release records in rechanneled stereo; this was mostly something pursued by the larger labels. Most small labels continued producing mono-only releases while they took a “wait and see” approach to stereo records. In the meantime, they just kept producing albums in mono only.

A few other record companies, mostly smaller labels, such as Chicago-based Vee Jay Records, occasionally released albums in true stereo, but they didn’t even bother with the pretense of producing records in rechanneled stereo for their older titles, for which stereo tapes weren’t available. Instead, they just took a shortcut – they printed covers that said stereo and they put mono records inside them and sold them as stereo records. And yes, they still charged buyers an extra dollar for them.

Phaseout of Mono Records

When stereo records were first introduced in the late 1950s, they were expensive, and required a significant cash outlay from buyers for both the stereo records themselves and the additional equipment required to play them. At that time, amplifiers used expensive vacuum tubes, but by the mid-1960s, most amplifiers had transistors, which allowed them to be sold at much lower prices than tube equipment.

When stereo records were first introduced in the late 1950s, they were expensive, and required a significant cash outlay from buyers for both the stereo records themselves and the additional equipment required to play them. At that time, amplifiers used expensive vacuum tubes, but by the mid-1960s, most amplifiers had transistors, which allowed them to be sold at much lower prices than tube equipment.

In 1960, only one album in 50 might have been sold in stereo, but by about 1966, the ratio of mono to stereo records in terms of sales became about 50-50, as stereo playback equipment became more affordable. By 1967, stereo records were outselling mono records by a hefty margin, and by 1968, most American record companies came to the conclusion that sales of mono records were decreasing to the point where it was not longer profitable to continue selling them.

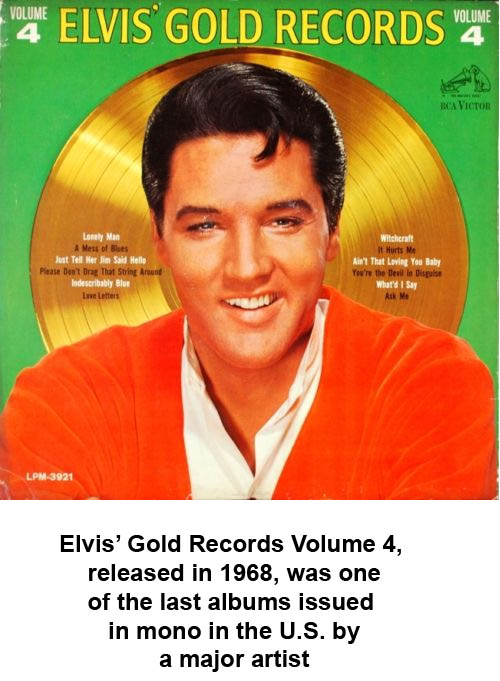

By early 1968, the major labels in the U.S. had either discontinued pressing records in both mono and stereo or they made mono records available on a special order basis only. By the end of the year, all of the major labels in the U.S. had stopped producing albums in both formats. Due to a lag in consumers buying stereo equipment in the UK, record companies there continued producing records in both stereo and mono until early 1970, though mono titles produced after mid-1968 are fairly scarce today.

The shift over the course of a decade from sales of mostly mono records to sales of mostly stereo records makes it interesting for record collectors. Early stereo records from the late 1950s are quite rare and are often quite expensive, while their mono counterparts are generally quite common and sell for quite a bit less money. On the other hand, mono pressings from 1967 and 1968 are comparatively scarce, and in some cases, exceedingly rare, and a few mono titles from major artists of that time, such as the Beatles, the Doors, the Monkees, Elvis Presley and Jimi Hendrix, sell for quite a bit more than their stereo counterparts today.

Although the record companies in the U.S. stopped pressing mono records in 1968 for sale to the public, they continued to occasionally press them for radio station use until about 1973. AM radio was still a popular format for music, and at the time, AM was mono-only. The record companies wanted to make sure that the radio stations had copies of their records that would sound they way they intended for them to sound when they were played on the radio.

Although the record companies in the U.S. stopped pressing mono records in 1968 for sale to the public, they continued to occasionally press them for radio station use until about 1973. AM radio was still a popular format for music, and at the time, AM was mono-only. The record companies wanted to make sure that the radio stations had copies of their records that would sound they way they intended for them to sound when they were played on the radio.

To ensure this, a few companies, notably Warner Brothers Records and Atlantic Records occasionally pressed special mono editions of albums for radio use only. They didn’t do this for all of their releases, and no one really knows how many copies of any given title might have been pressed in mono, but the number was fairly small.

These albums did not have a dedicated mono mix; the mono signal was simply “folded down” from stereo. Collectors are usually pretty eager to buy these pressings, as they are relatively rare and constitute an unusual addition to one’s collection. Such titles exist for artists such as King Crimson, Eric Clapton, the Byrds, Led Zeppelin, Yes, and Neil Young.

Why Collectors Like Mono Records

For collectors of artists who released albums during the decade or so when they were available in both stereo and mono, the question becomes, which one should you buy? The initial response from many novice buyers might be that if the recording was made in true stereo, then that’s the version to buy, as the mono version is simply an altered version of the stereo recording, made to accommodate people who didn’t own stereo equipment.

There’s some truth to that, but there are other factors to consider when planning a purchase. For popular music, there are some reasons to consider buying the mono version of an album. While stereo albums may have been recorded on two, four or eight track recorders, the material needed to be “mixed down” to either two track, for stereo, or a single track, for the mono pressings.

But songs also needed to be mixed to mono for radio purposes, and as AM radio was the predominant radio format at the time, it’s the mono versions of songs that were played on the radio. Since mono pressings outsold stereo pressings by a significant margin during the first half of the 1960s, artists and studio engineers usually spent a great deal more time mixing the mono version of their albums than they did the stereo version, simply because the mono version was the one that most buyers were going to hear.

Stephen Stills and Neil Young reportedly worked on the mono mix of the first Buffalo Springfield album themselves, while leaving the stereo mix of the album to record company employees. Similarly, members of the Beatles were heavily involved in creating the mono version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, while engineer Geoff Emerick was assigned the task of mixing the stereo version. He reportedly spent three hours on it and called it done.

Stephen Stills and Neil Young reportedly worked on the mono mix of the first Buffalo Springfield album themselves, while leaving the stereo mix of the album to record company employees. Similarly, members of the Beatles were heavily involved in creating the mono version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, while engineer Geoff Emerick was assigned the task of mixing the stereo version. He reportedly spent three hours on it and called it done.

Because of this type of thinking that was common in the record industry at the time, the mono and stereo versions of albums often sound dramatically different from one another. The stereo version of the hit single “Pleasant Valley Sunday” by the Monkees has backing vocals on it, while the mono version does not. The same applies to the Beatles song “Blue Jay Way,” where the backing vocals are missing on the mono version of Magical Mystery Tour.

Occasionally, one version of an album might even have a completely different version of a song on it than the other version. A good example of this is The Who Sell Out, by the Who, which has a different version of “Our Love Was” on the mono and stereo versions.

Another reason to consider buying the mono version of an album applies to how the album sounds. Many albums of the early 1960s were recorded on stereo equipment, but with the intention of releasing the album only in mono. The multitrack recordings were made to help mix the album to a nice-sounding mono version, but when played back in stereo, the instruments might not sound as if they’re properly placed. A good example of this is the first Beatles album, Please Please Me, where all of the instruments are heard on one channel but the vocal are heard in the other, with a “hole” in the middle of the soundstage.

This was also common with jazz recordings, and while the record companies issued the records in stereo, due to consumer demand, the albums were actually recorded with the mono mix in mind, and to the ears of many listeners, the mono version sounds more natural. Mono copies of many jazz albums of the late 1950s and early 1960s sell for much higher prices than their stereo counterparts, even though the stereo pressings may be the rarer of the two.

Finally, there becomes the issue of rechanneled stereo. Some “stereo” records of the early 1960s weren’t stereo at all, with artificially added delay, echo and reverb adding dramatic changes to the sound. In many cases, when mono albums were discontinued in the late 1960s, the record companies chose to make the rechanneled stereo versions of the albums the one that would continue to be available for sale.

In the case of artists such as the Who, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and Elvis Presley, that meant that from 1968 on, the only versions of albums originally recorded in mono were terrible-sounding rechanneled stereo albums with lots of reverb and echo. This was largely corrected in the 1980s, when many of these albums became available on compact disc, and the record companies wisely made the decision to release those albums in mono.

In the case of artists such as the Who, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and Elvis Presley, that meant that from 1968 on, the only versions of albums originally recorded in mono were terrible-sounding rechanneled stereo albums with lots of reverb and echo. This was largely corrected in the 1980s, when many of these albums became available on compact disc, and the record companies wisely made the decision to release those albums in mono.

For albums for which the options are mono or rechanneled stereo, collectors almost always opt to buy the mono version.

Mono versions of albums in the 1960s were often mixed differently than their stereo counterparts, which is one of the reasons that collectors are interested in acquiring them. Record companies have noticed this in recent years, and many albums of the 1960s have been reissued by the major labels in mono. Albums by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and the Jefferson Airplane and others are now available in the form of mono albums for the first time since the late 1960s.

These reissues have been well received, and part of the reason for the warm reception is the sound. As the stereo versions of many of these albums have been continuously available and in print for decades, the stereo master tapes are often in poor condition, resulting in current releases of stereo records that don’t sound nearly as good as they did when they were first released.

The mono albums, on the other hand, are being mastered from tapes that have largely been untouched for nearly 50 years. The resulting pressings often sound as good, or even better, than the original releases. Plus, in many cases, they’re a lot more affordable, as some of the harder to find mono pressings of the late 1960s sell for hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars on the collector market.

Why Collectors Like Stereo Records

Some collectors prefer stereo records, and there are reasons for that, too. Well-recorded stereo albums do provide a 3D sense of space and provide a “you are there” experience that mono recordings cannot.

Early stereo recordings were much simpler than those of today, which often involve 16, 32 or even 64 track tape recorders. The highly regarded RCA classical recordings of the late 1950s typically used only a few microphones and a three track tape recorder, and the results, performed with no overdubbing, often produce astonishingly realistic sound that RCA chose to call “Living Stereo.” Not surprisingly, there’s a lot of interest for such stereo recordings, while the mono pressings of those albums typically sell for modest prices.

Early stereo recordings were much simpler than those of today, which often involve 16, 32 or even 64 track tape recorders. The highly regarded RCA classical recordings of the late 1950s typically used only a few microphones and a three track tape recorder, and the results, performed with no overdubbing, often produce astonishingly realistic sound that RCA chose to call “Living Stereo.” Not surprisingly, there’s a lot of interest for such stereo recordings, while the mono pressings of those albums typically sell for modest prices.

There are even collectors who have interest in rechanneled stereo recordings. Granted, the records are not true stereo, but with their augmented sound, they do qualify as something unique and distinctly different from their mono equivalents.

As a rule, through much of the decade where mono and stereo records coexisted in the record stores, the stereo pressings command more attention and interest and sell for higher prices than their mono counterparts. The only exception to this comes in in 1967 and 1968, when the mono pressings became quite rare and are sought out for their rarity.

Lots of collectors, of course, simply attempt to buy both the mono and the stereo versions of albums by the artists that they collect, simply because that’s what collecting is about. If a collector collects the Beatles, for example, they’ll likely own both a mono and a stereo copy of Meet the Beatles or Revolver. Both have their merits, and because of the different mixes, there’s good reason enough to own them both.

Stereo Records vs. Mono Records Conclusion

While all records recorded and released today are stereo records, there was a period of about ten years when albums were released in both stereo and mono. Collectors are usually interested in both formats, for one reason or another, and there are good reasons for having an interest in both.

Mono and stereo albums offer different mixes from one another and sometimes, even different recordings altogether. Which one you want to listen to is a matter of personal preference, of course. On a good audio system, both mono and stereo records should provide a pleasing listening experience.

Click here to browse our selection of mono records.

Click here to browse our selection of stereo records.

Share this: