Vinyl Records Value

What are my records worth? That’s a common question these days as record albums are making a comeback among both casual music fans and hard core collectors. People are aware that some records are valuable, but most people don’t know exactly which records people are looking for or why they’re looking for them.

Establishing vinyl records value is an inexact science, and there are a number of factors that go into determining whether a given record is something that will bring a lot of money from a collector or something that would best be used as a place mat.

In this post, we’ll go over a number of factors that may determine the value of a particular record. Keep in mind that there are many factors that need to be taken into consideration, and it’s quite rare for a record to be valuable based on one factor alone. It’s usually a combination of things that add to a vinyl record’s value, and other factors can sometimes turn a valuable record into one that isn’t worth all that much seemingly overnight.

The list of qualities that can affect a vinyl record’s value is constantly changing, and the list shown below should not be considered to be definitive. As this post on vinyl records value is going to be fairly lengthy, we’ll divide it into sections.

Vinyl Records Value Categories

Click any of the links below to jump to each category:

Age of the Record

Who is the Artist?

Overall Scarcity

Sealed Records

Autographed Records

Commercial vs. Promotional Issues

Small Label vs. Major Label

Label Variations

Mono vs. Stereo vs. Quadraphonic

Colored Vinyl and Picture Discs

Picture Sleeves

Acetates and Test Pressings

Foreign Editions

Limited Editions

Withdrawn Releases

Counterfeit Records

Reissues and Falling Prices

Condition of the Record

Finding Recent Prices

Conclusion

Featured Products

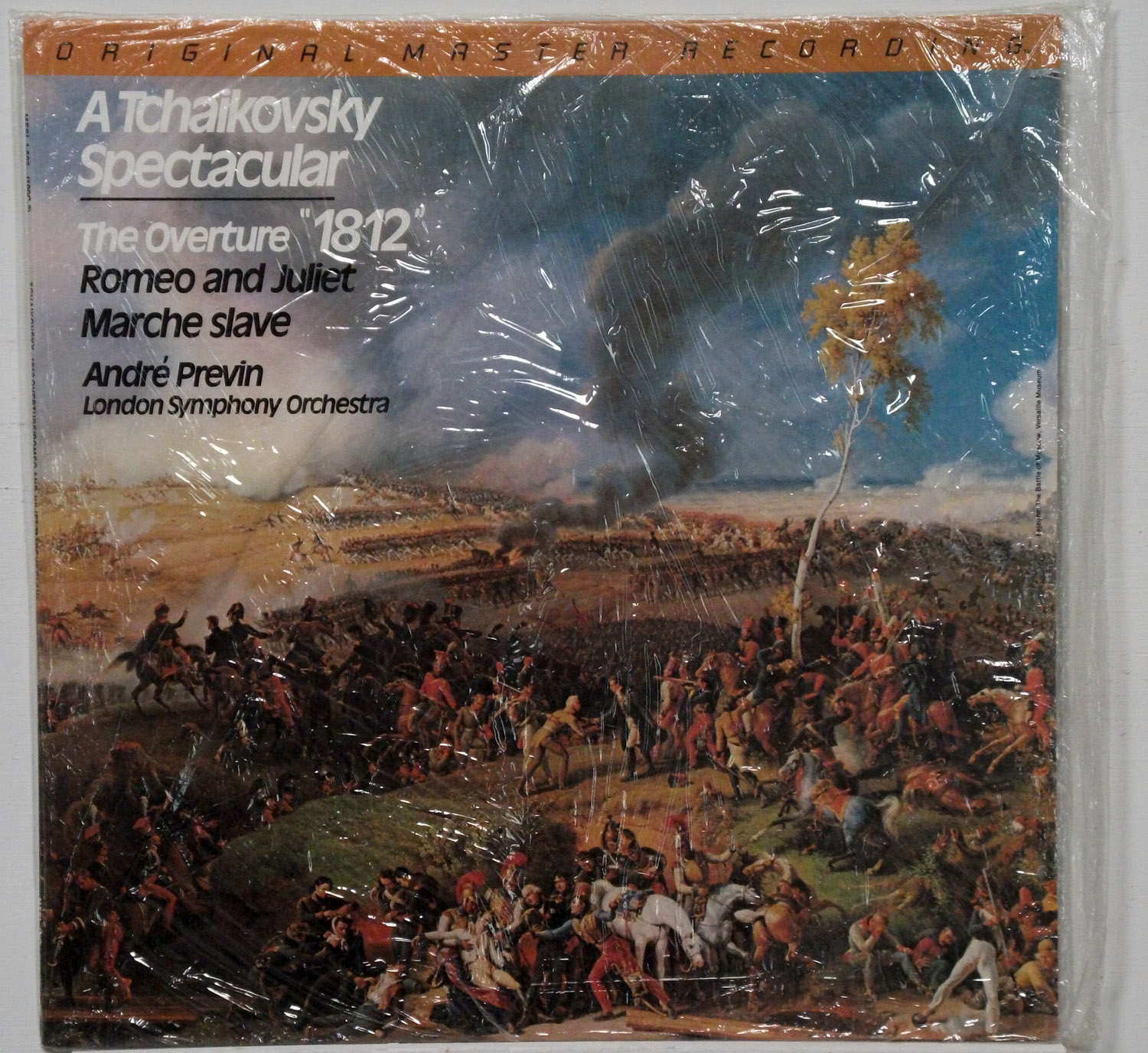

-

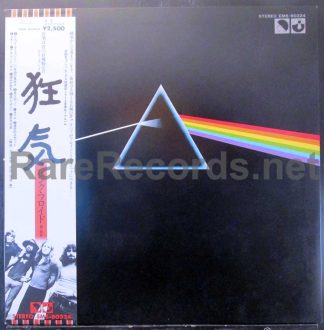

Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon complete 1974 Japan LP with obi

$195.00Free U.S. shipping! A 1974 Japanese pressing of The Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd, complete with obi, booklet, posters and postcard.Add to cart -

Miles Davis – Porgy and Bess sealed U.S. mono LP

$295.00Free U.S. shipping! A still sealed mono U.S. pressing of Porgy and Bess by Miles Davis, with the record still sealed in the plastic inner sleeve.Add to cart -

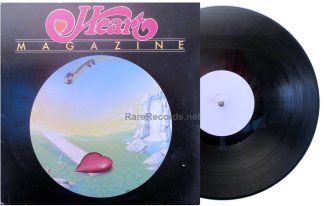

Heart – Magazine withdrawn 1977 U.S. TEST PRESSING LP with disclaimer and alternate mixes

$295.00Free U.S. shipping! An original U.S. test pressing of the withdrawn 1977 version of Magazine by Heart, with the contractual disclaimer on the cover and alternate mixes.Add to cart

Click here to visit our rare records store. (new window)

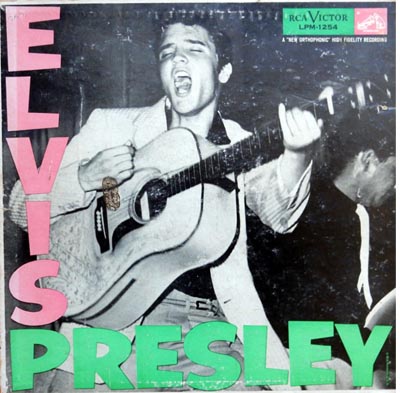

Many of the people we’ve spoken to about records over the years have the impression that “old records” must be worth more than new ones. While the age can have an effect on a vinyl record’s value, it’s one of the less important factors. Releases from early in the career of a famous artist may have more value than those from later in their careers, particularly if they didn’t become famous right away. A good example of this would be the recordings of Elvis Presley. While his first five records for the Memphis-based Sun label sold reasonably well for their day, their sales figures were minuscule compared to those of his later releases on RCA, making the Sun versions fairly valuable.

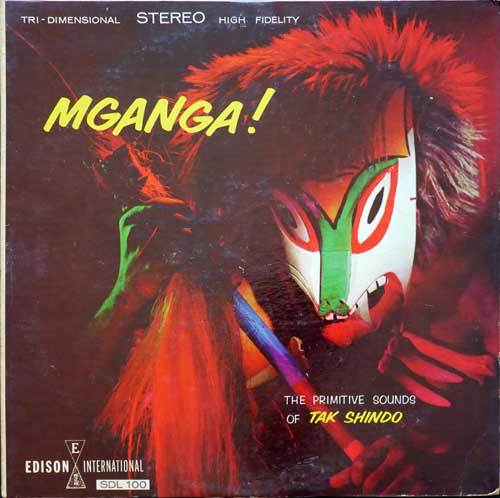

On the other hand, records by artists that are not of interest to collectors will have little value, regardless of age. There are many records in the easy listening genre from the 1950s, such as those by Ray Conniff or Percy Faith, that are now some 60 years old, but they still sell for only a couple of dollars in most used records stores, provided they bother to offer them for sale at all.

“Old records” may have some value, but as a rule, it’s not because they’re old. It’s because of something else.

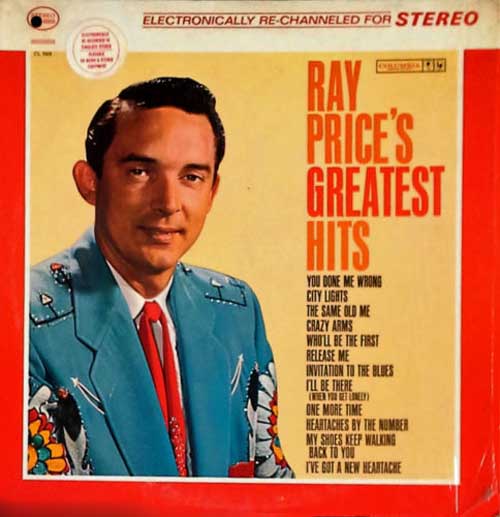

This should be obvious, but the artist in question will be a big factor in determining the value of a record. While tens of thousands of artists have released records since the invention of the medium, not all of them interest the public in equal measure.

Some artists are simply more popular as well as more collectible than others. Artists in the rock, blues, jazz, classical and soul categories tend to be more collectible than those in the easy listening, country, spoken word or comedy categories.

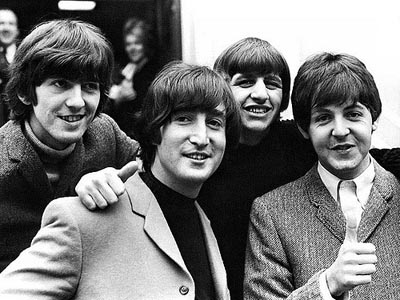

Some artists tend to have a longtime following, while others are popular only while they are actively recording. With the former, such as Elvis Presley, Pink Floyd, blues singer Robert Johnson, or the Beatles, many of their records remain both valuable and highly collectible long after they stopped recording or even after their deaths.

Other artists may have had records with high values only during the time they were recording, with prices in the collector market dropping considerably after they finished their careers or when they passed away.

In the late 1970s, for example, Todd Rundgren and the Cars were highly collectible, but these days, there’s little interest in their recordings. On the other hand, records by the Beatles are selling for the highest prices ever and prices remain steady more than 50 years after they released their last album.

Exceptions to that exist; that can come in the form of artists who were never particularly popular, but who were influential in the industry. That’s true of artists such as Robert Johnson, the Velvet Underground, or the Stooges. None of these artists were very successful and their records sold poorly when new. All three were enormous influences on other musicians, however, and as a result, their records sell for surprisingly high prices today.

Still, as a rule, popular artists will have records with higher values than obscure ones.

This factor is pretty straightforward when it comes to vinyl records value; records that sold well and are quite common are going to be less valuable than records that sold poorly or are hard to find. A lot of albums sold in the 1970s and early 1980s sold millions of copies when new, and as such, it isn’t difficult to find copies in nice, playable condition.

That being the case, such records aren’t likely to sell for very much money in the collectors market.

On the other hand, even records that sold well when new can become scarce in time, especially when one takes the condition of the record into account. Albums by Elvis Presley and the Beatles sold millions of copies when they were first released, but finding nice original copies of those records now can be difficult, as many have been thrown away or damaged through heavy play or abuse.

People have tended to take better care of their records in recent decades, so it’s a lot easier to find a nice copy of a 1980s album by Bruce Springsteen than it is to find a near mint 1960s album by the Rolling Stones, for example.

“Common” is also relative; records that sold well in the 1950s and 1960s still sold in substantially smaller quantities than those sold in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1950s, it was rare for even a popular album to sell much more than a million copies. By the 1980s, albums selling more than 5 million copies were relatively common.

What the “common vs. scarce” factor means is that the most valuable record by a particular artist may not be their best-known title, but rather one that was disregarded by the public and/or critics when originally released, making it relatively scarce today. A good example of this would be Music from the Elder by Kiss, released in 1981. Released after a string of best-selling albums, Music from the Elder had a different sound from their previous releases and offered no hit songs and no songs that regularly received airplay. As a result, the album sold poorly and soon went out of print.

The group went back to making records that were similar to their earlier releases and sales of subsequent albums were brisk, making the now hard-to-find Music From the Elder a collector’s item.

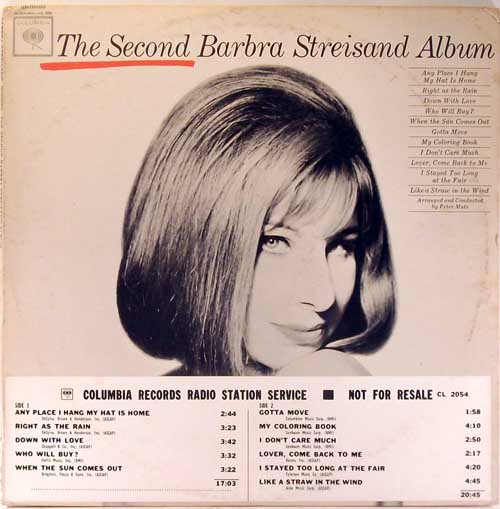

One factor that’s of vital importance in determining a vinyl record’s value is condition, which we’ll discuss at length later. Because the condition of a record is held to be important by collectors, the ideal example of a record to own, in the eyes of many collectors, would be one that has never been played at all. Because of this, collectors will often pay a huge premium for sealed, unopened examples of records they are seeking.

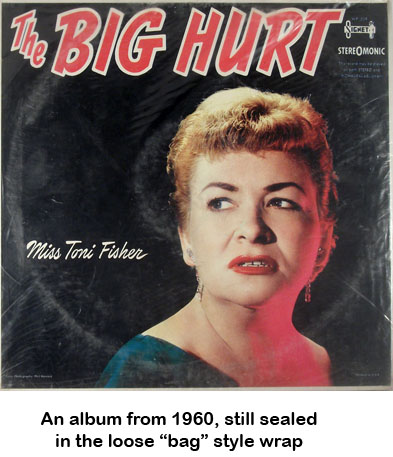

When record albums were first offered in the late 1940s, they were sold without any external wrapping on the cover. Customers in record stores could remove the records from the cover and many stores would even allow them to play the records to help them make a buying decision. This led to problems with both theft and damage, and by the early 1960s, a number of large retailers started sealing their albums in plastic bags. Eventually, this practice was picked up by the major record companies, who began protecting their covers with shrink wrap.

When record albums were first offered in the late 1940s, they were sold without any external wrapping on the cover. Customers in record stores could remove the records from the cover and many stores would even allow them to play the records to help them make a buying decision. This led to problems with both theft and damage, and by the early 1960s, a number of large retailers started sealing their albums in plastic bags. Eventually, this practice was picked up by the major record companies, who began protecting their covers with shrink wrap.

In general, a copy of an album that is still in original, unopened shrink wrap will sell for a lot more money than one that is in opened condition, even if the opened copy has not been played.

The difference in price can range from modest to quite significant, depending on the artist and title. A sealed copy of a relatively recent release may carry a small premium over an opened copy, but older and/or more desirable titles may exhibit a substantially larger premium. Sealed copies of older albums by the Beatles might sell for as much as ten times the price of an opened example, for instance.

This is a case where age can affect vinyl records value, as the older an album is, the harder it is to find a copy that has never been opened or played.

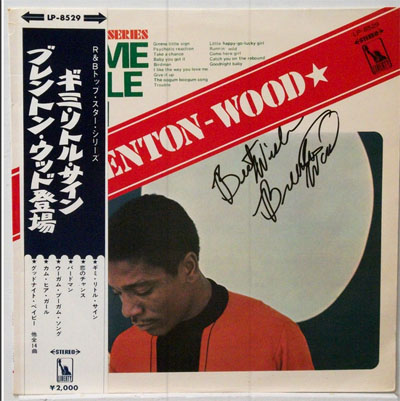

One factor that can influence vinyl records value is having the autograph of the artist on it. While autographed albums and single aren’t particularly common (while forgeries of them are), they usually do command a premium over regular copies of the record that are not signed.

Autographed records that are personalized, such as “To Jane, best wishes…” tend to sell for less money than those that simply have the artist’s signature on it. When it comes to musical groups and autographs, albums that are autographed by the entire group will sell for substantially higher prices than those with the signatures of some, but not all, members.

Autographed records with provenance, such as a photograph of the artist signing the record, tend to bring the highest prices of all.

Commercial vs. Promotional Issues

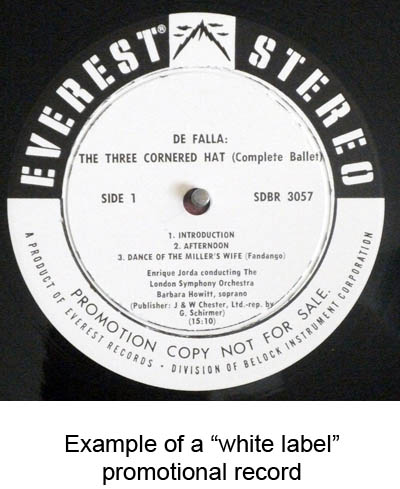

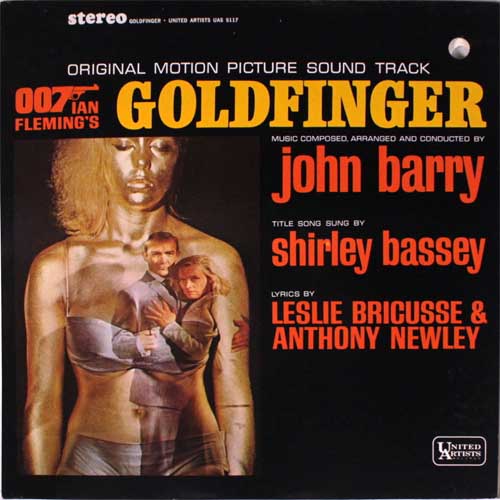

One factor that can affect vinyl records value is if the record in question is a promotional issue, as opposed to a commercial, or “stock,” copy of the record. Promotional, or “promo,” copies of a record are often identified in some way, and they often have a special label that indicates that the particular records was made for promotional, or radio station, use. While the labels on most records are colored, many promotional issues have white labels, which has led to the term “white label promo” being used among collectors.

Promotional copies of records are usually pressed before retail, or “stock” copies to ensure that they reach radio stations prior to the commercial release of the record. They are also pressed in relatively small quantities compared to stock copies of the same records. While an album may sell in the millions, there may be only a few hundred promotional copies made of that same record, making them collector’s items.

Promotional copies of records are usually pressed before retail, or “stock” copies to ensure that they reach radio stations prior to the commercial release of the record. They are also pressed in relatively small quantities compared to stock copies of the same records. While an album may sell in the millions, there may be only a few hundred promotional copies made of that same record, making them collector’s items.

Sometimes, promotional copies of a particular record may be different from the stock counterpart. The promotional copies of the Beatles’ single “Penny Lane” had a different ending than the version of the song on the stock copies of the single, making these rare copies quite valuable in comparison to the million-selling stock counterpart.

On other occasions, a record may be issued only as a promotional item. Such albums may be live recordings, made for radio broadcast, or perhaps compilation albums, again intended to stimulate airplay. These “promo-only” releases are usually sought after by collectors, though the interest in them will be directly related to the interest in the artist. A promo-only Rolling Stones record, for example, will attract far more interest from collectors than one by Andy Williams.

As a rule, a promotional copy of any record will command higher prices in the collector’s market than the stock counterpart, though there are occasional situations where the opposite is true. Some records have sold so poorly in stores that the promotional copies are actually more common than the stock counterparts. A good example of this is the Beatles’ first single, “My Bonnie,” which was credited to Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers. Promotional copies with a pink label, while relatively rare, are probably ten times more common than the stock copies with black labels, of which fewer than 20 copies are known to exist.

We have written an extensive article about white label promo records; you can read it here. (new window)

This issue of scarcity comes into play when one looks at whether a particular record was released by a small, regional label or a large national one. Larger labels have national distribution and multiple pressing plants, and popular records might be pressed in the millions. Smaller labels might press only a few hundred or several thousand copies of a particular record.

There are examples of records being initially released on small labels and then later released on larger labels when the small record company negotiated a distribution deal with the larger label in order to sell more records. An example of this would be the 1963 surf album Pipeline by the Chantays, which was originally released on the California-based Downey label. When the song became a hit, Downey struck a deal with the nationally distributed Dot records to have them release the album instead. Today, copies of the album on the Downey label are far harder to find than their Dot counterparts, and sell for higher prices.

Sometimes an artist will release records on a small label and then move to a larger one. In these cases, their earlier releases tend to be more collectible than their later ones. The country group Alabama released a couple of albums on the small LSI label under the name “Wild Country” before changing their name and moving to the large RCA label. As the records by the group issued by RCA sold quite well, they tend to sell for modest prices. The two albums on LSI, on the other hand, are quite rare and sell for several hundred dollars or more when they’re offered for sale.

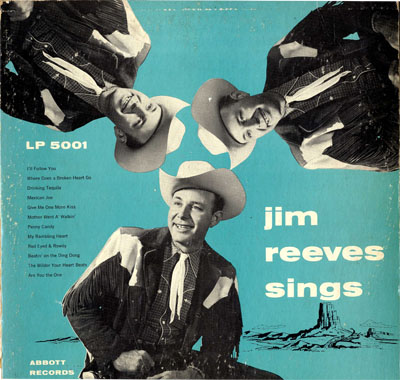

Another example, also in the country genre, is the first album by Jim Reeves. His first album, Jim Reeves Sings, was issued in 1956 on the small Abbott label. When that album began to sell well, Reeves moved to major label RCA. While his RCA albums sell for modest prices, his lone album on Abbot has sold for as much as $1000.

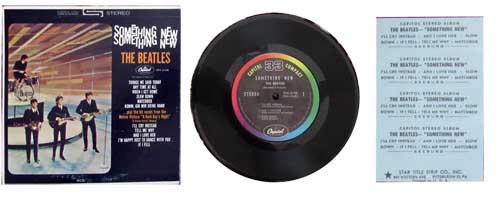

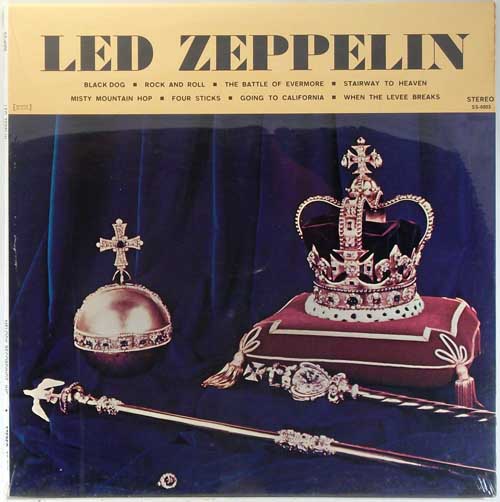

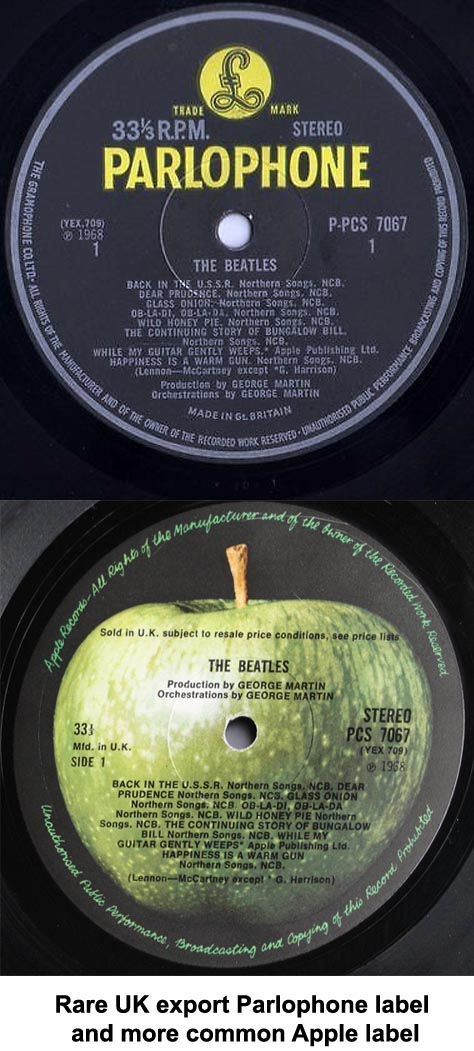

A significant factor in determining a vinyl record’s value is the label on the record itself. A given album or single might have been released with several different labels on the disc itself, even among releases by the same record company.

Record companies often change the appearance of the labels used on their records. While it has happened less often in recent decades, changes in label art an appearance were quite common among the major labels during the 1960s and 1970s.

Records by the Beatles, for instance, were released by Capitol Records on a black label with a rainbow colored perimeter, a green label, a red label, a custom Apple label, an orange label, a purple label, and a new version of the original black label, all over a period of less than 20 years.

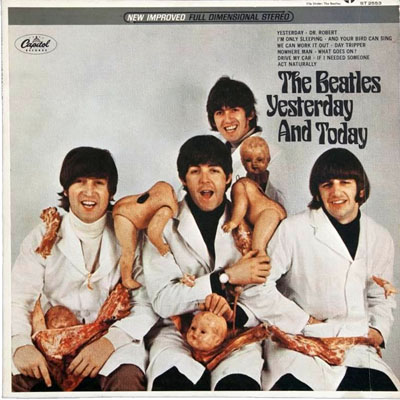

As a rule, collectors tend to favor original pressings, so for a given title, the most desirable label variation would be whichever one was in use on the day the record was originally released for sale to the public. There are exceptions to this, however. The red Capitol label mentioned above was commonly used in the early 1970s for a number of titles, but was never intended to be used for records by the Beatles. A few copies of the band’s Revolver and Yesterday and Today albums were accidentally issued with that label, and despite not being “original” issues, they do sell for quite a lot of money on the collector’s market.

Sometimes, minor differences on labels can make a difference, as well. The first copies of Meet the Beatles to be sold in America were rushed to the stores without including publishing information for the songs on the record. While later copies had either “BMI” or “ASCAP” after each song title, the very first issues of the album sold in stores lacked this text. While this might seem to be a minor matter, the difference in value between a copy that lacks the text and one that has it can be more than $1000, depending on condition.

As many albums by popular artists have remained in print for many years, or even decades, the label on the record in question is often a significant factor in determining that vinyl record’s value.

Mono vs. Stereo vs. Quadraphonic

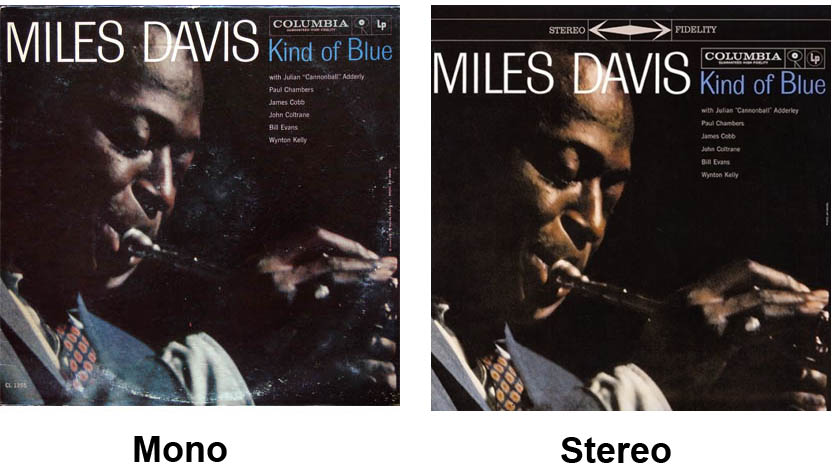

A significant factor that can affect a vinyl record’s value is the format. Until 1957, records were sold only in mono. Between 1957 and 1968, records were usually sold in both mono and stereo, and between about 1972 and 1976, a few records were available in 4 channel quadraphonic sound. During the time when records were sold in more than one format simultaneously, one of the formats was usually pressed in smaller quantities than the other. Mono records were more common than their stereo counterparts in the early 1960s, for instance, but were the harder variation to find by 1968. Quadraphonic pressings were always intended for a niche market, and never sold in large quantities, except in the few cases where all copies of a particular title were encoded in quadraphonic sound.

A significant factor that can affect a vinyl record’s value is the format. Until 1957, records were sold only in mono. Between 1957 and 1968, records were usually sold in both mono and stereo, and between about 1972 and 1976, a few records were available in 4 channel quadraphonic sound. During the time when records were sold in more than one format simultaneously, one of the formats was usually pressed in smaller quantities than the other. Mono records were more common than their stereo counterparts in the early 1960s, for instance, but were the harder variation to find by 1968. Quadraphonic pressings were always intended for a niche market, and never sold in large quantities, except in the few cases where all copies of a particular title were encoded in quadraphonic sound.

While the value of a mono record in relation to its stereo counterpart will depend on when the record was released, quadraphonic copies are almost always worth more money than the same album in stereo.

The topic of mono vs. stereo is a complex one, and we have covered that in detail in another article which you can read here. (new window.)

Colored Vinyl and Picture Discs

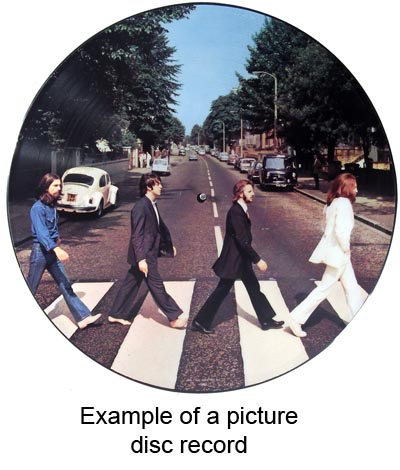

While most records are pressed from black vinyl, sometimes other colors are used. On rare occasions, a special process is used to create a picture disc, which has a photograph or other graphics actually embedded in the record’s playing surface. With few exceptions, colored vinyl and picture disc pressings are limited editions, and are usually far harder to find than their black vinyl counterparts.

While most records are pressed from black vinyl, sometimes other colors are used. On rare occasions, a special process is used to create a picture disc, which has a photograph or other graphics actually embedded in the record’s playing surface. With few exceptions, colored vinyl and picture disc pressings are limited editions, and are usually far harder to find than their black vinyl counterparts.

Both colored vinyl pressings and picture discs have been issued as commercial releases and as promo-only releases. In the early 1960s, Columbia Records would occasionally press promotional copies of both singles and albums on colored vinyl (we’ve seen red, yellow, blue, green, and purple) in order to grab the attention of radio programmers.

In the late 1970s, picture discs were often pressed as promotional items and became quite popular among collectors. Most of these were pressed in quantities of only a few hundred copies.

More often, colored vinyl and picture disc records are issued as limited edition pressings, created to spur interest among buyers. Most of these titles are also available on regular (and more common) black vinyl.

As with everything else on this list, there are occasional exceptions to the rule. Elvis Presley’s last album to be issued while he was alive was Moody Blue, which was pressed on blue vinyl when originally released. A couple of months later, RCA Records began to press the album on regular black vinyl as a cost-cutting move, which would have made the earlier blue vinyl pressings relatively rare and desirable as time passed. Shortly after this decision was made, Elvis passed away, and the label made the decision to return to using blue vinyl for that album, and all pressings for the next ten years or so were issued on blue vinyl. In the case of Moody Blue, it’s the black vinyl pressings, which were only pressed for a short period of time, that are the rare ones.

We’ve written articles about colored vinyl and picture discs, and you can read it here:

Colored vinyl article (new window)

Picture disc article (new window)

While vinyl record albums usually include printed covers, most 45 RPM singles do not, as they were generally issued in plain paper sleeves. It was not uncommon, however, for singles to be issued in special printed sleeves bearing the title of the song, the name of the artist and perhaps a graphic or photograph. These are known as picture sleeves or title sleeves, and most of the time, these picture sleeves were available only with the original issues of the records. While not intended as limited edition items per se, picture sleeves were designed to spur sales and were often discontinued once sales of the record began to increase.

For various reasons, some picture sleeves are harder to find than others, and there are a number of records, some by famous artists, where certain picture sleeves are rare to the point where only a few copies are known to exist. Some picture sleeves, such as “Street Fighting Man” by the Rolling Stones, which was withdrawn prior to release, can sell for more than $30,000.

Others are rare, but not to that degree. The picture sleeve for the Beatles’ single “Can’t Buy Me Love” were commercially available, but were only printed by one of Capitol Records’ pressing plants, making it available only for a short time and only in the eastern United States. It’s one of the rarest commercially available Beatles picture sleeves, and mint copies have sold for more than $1000.

This is one of the factors that pretty much has no exceptions; a record with a picture sleeve is always more valuable than the same record without one.

While the majority of records are standard issues that were manufactured with the intention that they be sold in stores, some are pre-production versions that were made for in-house use at the record companies prior to making the stock pressings.

While the majority of records are standard issues that were manufactured with the intention that they be sold in stores, some are pre-production versions that were made for in-house use at the record companies prior to making the stock pressings.

Acetates, or lacquers, as they are more properly known, are records that are individually cut on a lathe by a recording engineer. The recordings are cut on metal plates that are coated with soft lacquer. Acetates are the first step in the process of making a record, as they can be plated with metal and used to make stampers for production of the copies sold in stores.

They can also be played on a turntable and are often used to evaluate the sound of a song or an album prior to putting it into formal production. While acetates can be played as one would play any regular record, they don’t wear particularly well and will become quite noisy after only a few plays.

On rare occasions, acetates have been sent to radio stations as promotional items when regular pressings were not yet available.

As acetates are cut one at a time, they are understandably rare, and command a high value in the market place as they are both rare and unusual.

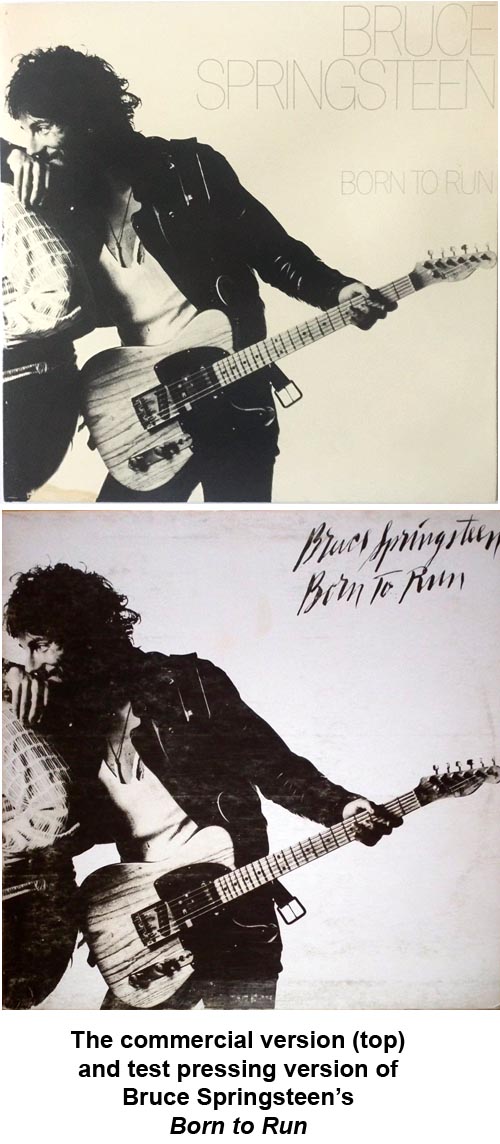

Test pressings are a bit more common than acetates, and are made to test stampers prior to mass produced production runs. They are usually the first pressings made from a set of stampers, and can be distinguished by their labels, which will differ from those used on stock pressings. Test pressings may have blank white labels or they may have special labels that indicate that they are test pressings. These custom labels usually have blank lines printed on them so that the people working with them can write the title and artist on the labels by hand.

As with acetates, test pressings are usually used for evaluation purposes by record company personnel, though they are occasionally sent out as promotional items. As they are rather unusual and limited in production to just a handful of copies, test pressings are highly regarded and sought out by collectors. Sometimes, test pressings may contain different versions of one or more songs from the commercially released albums. This can also add to their value.

Test pressings of Bruce Springsteen’s 1975 album Born to Run were sent to radio stations in a cover that had the album title in a different font from commercial releases. These so-called “Script Cover” pressings of the album have sold for more than $1000.

We have written a more in-depth article about test pressings and acetates. You can read it here. (new window)

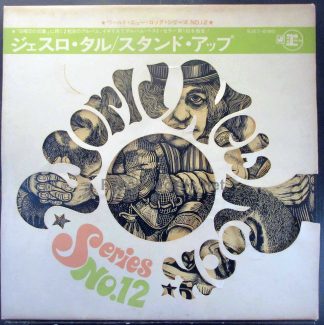

Records pressed in foreign countries are often of interest to record collectors. While most collectors are interested in records from the country where they live, a lot of them are interested in owning anything unusual by the artists that interest them.

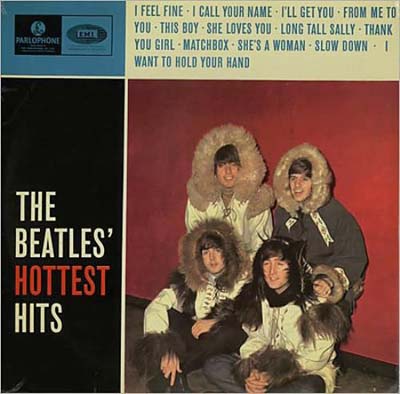

Most record albums are designed by record companies in either the United States or Great Britain, and most releases from either country are nearly identical. Other countries, however, have been known to create dramatically different versions of records from the U.S. or UK counterparts.

Sometimes, foreign pressings may have different titles, or different covers from the more common versions from the U.S. or UK. On other occasions, record companies in other countries may choose to press albums on colored vinyl.

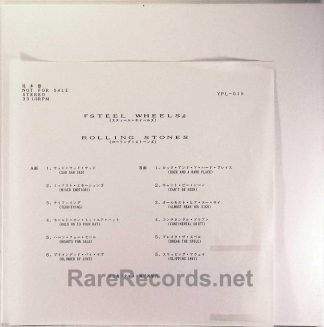

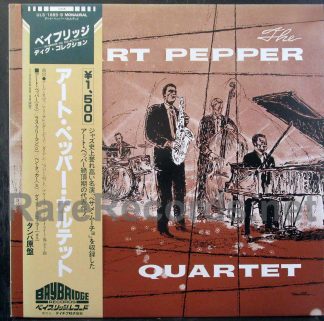

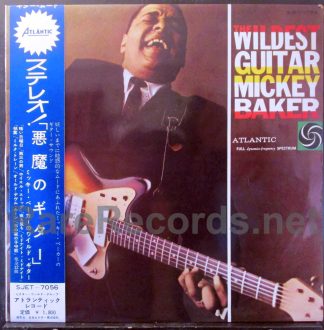

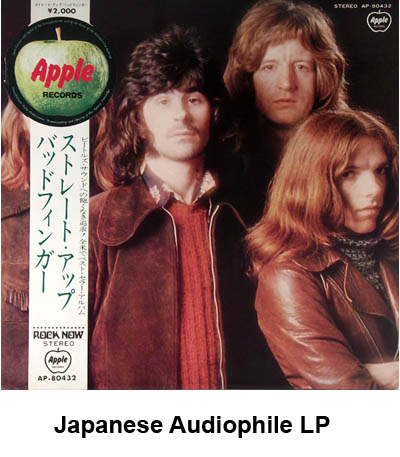

Many albums from Japan from the late 1950s through the early 1970s were pressed on dark red vinyl. Japanese pressings were also issued with a paper sash, or “obi,” that wrapped around the cover and provided information for the buyer in Japanese.

These pressings are highly regarded by collectors for both their unusual appearance and their sound quality.

If an artist is not from the United States, collectors will often seek out records from the artist’s country of origin. While many American Beatles records are worth a lot of money, so are those from Great Britain, as the band released records there prior to releasing them in the U.S.

Prices for foreign (non-U.S.) records can vary widely, depending on age, condition, and all of the other factors mentioned in this article. In general, collectors in the United States will always be interested, to some degree, in any foreign record by artists whose records they collect.

We’ve written a detailed article about Japanese records. You can read it here. (new window)

While scarcity can be a major factor in a vinyl record’s value, intentional scarcity can affect it even more. While limited edition pressings of albums are a relatively new thing, they are now quite common, with record companies intentionally limiting releases to a few hundred or a few thousand copies.

In past decades, when records were the predominant format for selling music, record companies were content to sell as many copies as possible of a given title. In recent years, records have become more of a niche item, and record companies are somewhat hesitant to spend the money to master, press, and distribute them. By producing only a limited number of a given title, and by making it publicly known that production will be limited to xxx number of copies, the record companies have a greater likelihood of having a particular title sell out quickly, rather than sitting on a shelf for a period of months or years.

Sometimes, these limited editions are individually numbered, while most are not. Sometimes, a limited number of copies of a given album will be pressed on colored vinyl, with a larger number pressed on black vinyl. In some cases, such as with the soundtrack album to the 2010 film Inception, all copies are colored vinyl and they are numbered as well.

Limited edition pressings by most any artist will have some value above the original selling price, as record companies are unlikely to issue limited edition pressings if there is no established market for them.

The exception to this would be records from companies that do not ordinarily release records, such as the Franklin Mint. Over the years, the Franklin Mint has released a number of recordings as limited edition sets, usually spanning many volumes. Most of these recordings were also pressed on colored vinyl and the sets were marketed in mass media to consumers who were not record collectors. These recordings have little value unless they are offered in complete sets, some of which came with as many as 100 records.

Occasionally, record companies release an album or single, only to change their mind and withdraw it from general release. This can happen for a number of reasons, ranging from a corporate decision that may or may not have anything to do with the record itself, a decision by the artist to change the product after release, or even an announcement by prominent retailers that they will refuse to sell the record as released.

Regardless of the reason for withdrawing the record from circulation, such releases will naturally be scarce, hard to find, and in demand among collectors. More often than not, withdrawn releases will also command substantial prices on the collector market.

Listed below are a few examples of record albums which were withdrawn from the market shortly before or shortly after being released to stores.

Angel – Bad Publicity – The 1979 album Bad Publicity had a cover that depicted the band having a raucus party in a hotel room. After only a handful of copies had been issued as promotional items, the album was withdrawn, retitled to Sinful, and released with completely different artwork showing the band in white suits against a white background.

Prince – The Black Album – In 1987, Prince intended to release an untitled album that had an all-black cover on which neither a title nor the name of the artist appeared. The so-called “Black Album” was withdrawn prior to release at the request of Prince himself, for reasons that remain unclear to this day. A few copies have leaked out over the years, and they have sold for as much as $25,000.

The Beatles – When retailers complained about the original cover art for the Beatles’ 1966 album Yesterday and Today, which showed the band sitting on a bench with broken dolls and raw meat, Capitol Records ordered all copies returned from stores and radio stations. The cover was replaced by a picture of the band sitting around a steamer trunk.

This so-called “Butcher Cover” is perhaps the best known record in all of record collecting, and copies have sold for thousands of dollars.

We have written an extensive article about the Beatles Butcher cover. You can read it here. (new window)

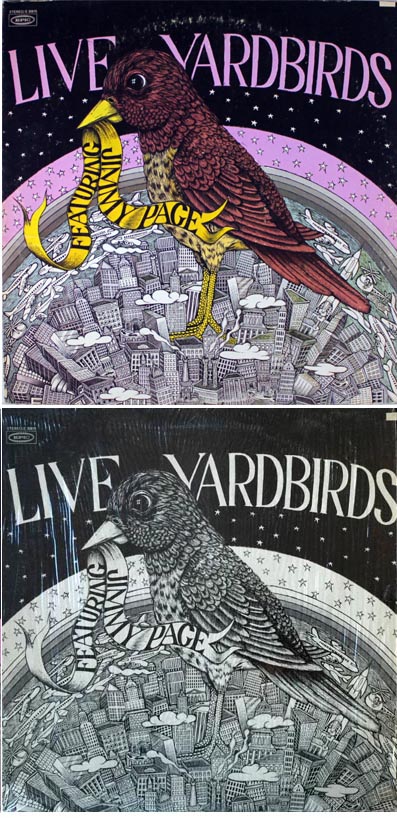

Whenever there’s a commodity that is worth money to people, there are unscrupulous people who try to take advantage of them by forging that commodity. Paintings have been forged, currency has been counterfeited, and unfortunately, so have many rare records.

While there are many factors that go into determining vinyl records value, perhaps none is more important than the need for the record to be an original pressing and not a counterfeit pressing created at a later date to resemble the original issue.

Counterfeit records first appeared on the market in the late 1960s or early 1970s and while the early attempts were rather obvious and fairly crude, technology has improved in recent years, making many counterfeit records difficult for the layman to identify. The practice isn’t limited to rare or valuable titles, either, as a number of mass-produced titles were counterfeited in the late 1970s. These titles were sold by chain record stores alongside the legitimate record company issues.

If a record routinely sells for a lot of money, there is a good chance that the title in question has been counterfeited. Many albums by the Beatles, along with other popular artists such as the Yardbirds, Elvis Presley, and Pink Floyd, have been counterfeited. In a few cases, such as the Beatles album Introducing the Beatles, counterfeit copies may actually outnumber the real ones.

It goes without saying that a counterfeit copy of a rare record will have limited value when compared with an original pressing.

We have written an extensive article about counterfeit records. You can read it here. (new window)

One factor that can significantly affect a vinyl record’s value is the availability of reissues. In the 1950s through the mid-1970s, record companies kept close tabs on whether an album was selling well or poorly. Poor selling albums were usually removed from the catalog and existing copies were sold at a discount. Starting in the 1980s, record companies took a different approach, and reduced the prices of slow-selling records, keeping them in print but offering them for sale at a lower price point.

Collectors often become interested in records that have gone out of print, and the prices for these no longer available titles can get quite high, depending on the artist and title. In these cases, collectors are usually paying high prices simply to hear the music. Record companies do pay attention to such market trends, and today, it’s quite common to see newly-pressed reissues of albums for sale that haven’t been available on the market in decades.

In the case of some albums, which may have only been originally for sale from small record companies, these reissues might actually sell more copies than the original album. When an album is reissued, the original vinyl record’s value usually falls in the marketplace. While some collectors remain interested in owning an early or an original pressing of a recently reissued album, there are others who are only interested in hearing the music, and will be happy to own a reissued version of the album instead.

Reissues can often affect a vinyl record’s value dramatically, and sometimes, the price of original pressings can drop as much as 90% when a formerly rare album again becomes available as a newly-released record.

While all of the factors listed above are important when it comes to evaluating a vinyl record’s value, perhaps none is as important as the condition of the record. Most mass produced records sold over the past 60 years or so have been poorly cared for by their owners. They may have been played on low-quality equipment, stored outside of their covers, and handled by their playing surfaces, rather than their edges.

Record changers, which were phonographs that were capable of playing up to a dozen records in sequence, were popular in the 1960s and 1970s and were particularly prone to adding scratches and abrasions to a record’s playing surface. Many covers were poorly stored, leading to ring wear or splits in the covers. Furthermore, owners often wrote their names or other information on the record’s cover or label.

Collectors are interested in buying records in the best possible condition, and ideally, they’d like to own copies of all of their records in the same condition in which they were originally sold – mint and unplayed, with pristine covers.

Finding a copy of any record that is more than 20 years old in such condition is quite difficult, and the value of a record can vary widely depending on its condition. In the case of many records from the late 1950s and early 1960s, finding worn and nearly-unplayable copies of a particular record might be relatively easy, while finding one in mint condition may be nearly impossible.

In the case of such records, a mint copy might sell for 50 times as much money as a worn-out copy of the same record.

When it comes to a vinyl record’s value, condition is paramount, and worn copies of a record usually sell for modest amounts of money except in the cases of items that are rare to the point of being unique.

In the case of records that are common to moderately rare, any copy that isn’t in nearly new condition may have little to no value at all.

While some collectors are willing to accept “filler” copies of a rare record in poor to average condition until they find a better copy, most buyers prefer to buy only once, and will hold out for the best possible copy they can find.

What does all of this mean? It means that if you’re someone who has a box of “old records” and you want to know about those vinyl records’ value, you’ll likely discover that they’re common titles in average to poor condition and they’re likely not worth very much money.

On the other hand, if you have a rare record that is also in exceptionally nice condition, you’ll likely be able to sell it for a premium price.

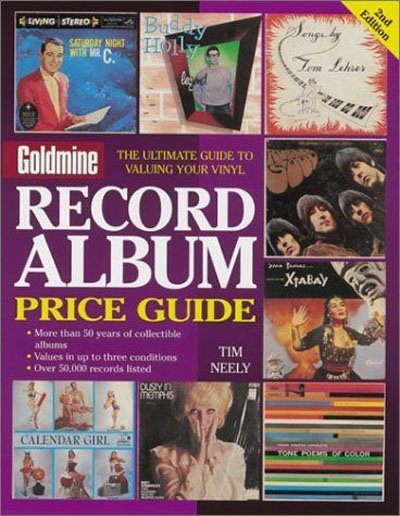

Starting in the late 1970s, the easiest way to find out about vinyl records value was to consult a price guide. Over the past 40 years, a number of books have been published every other year or so that list the value of certain types of records. There are price guides for rock albums, jazz albums, classical albums, 45 RPM singles, country records, and soundtrack and original cast recordings. There are also specialty price guides for records from Japan, records by the Beatles and records by Elvis Presley.

While these guides have served collectors and sellers fairly well, the books are bulky, somewhat expensive, and have a tendency to become outdated rather quickly. That’s not to say that they aren’t useful; on the contrary, they serve as valuable references. Furthermore, even the outdated price guides can offer insight as to how a vinyl record’s value has increased over time. It’s amusing to look at price guides from the late 1970s to see how albums that might sell for $1000 today were once listed as having a value of $35 or so.

Record price guides are still published today and they’re still useful tools. On the other hand, there are also some online tools that can provide some more accurate and up to date information regarding vinyl records value. Several sites, for example, monitor the sales of records on the eBay auction site and archive them, making it possible for you to see what a particular records might have sold for yesterday, or last month, or even five years ago.

As there are millions of records for sale on eBay, including multiple copies of most records at one time, the marketplace is somewhat of a buyer’s market, which means that the prices of most records sold on the site are somewhat lower than they might be in a record store or in a private transaction between two collectors.

Still, the millions of record sales on the site each year do provide some good insight into overall vinyl records value, and can also show trends over the past decade or so. This makes it easy to see if a particular record is increasing in value over time or going down as interest sometimes wanes.

While there are a number of different sites that track and archive record sales on eBay our favorite is:

Popsike.com – This site is free to use for a limited, but unspecified, number of searches. After a certain number of searches, you’ll be asked to register, which is free. If you exceed a further (unspecified) limit, you’ll be asked to subscribe. Currently, the cost of subscribing to Popsike is about $35 per year, though most users will never use the service enough to reach the threshold that requires paying a subscription fee.

Popsike’s home page has a few lists of popular searches, as well as lists of recent sales in certain popular categories, such as blues, Beatles, classic rock, jazz, and classical. You can search by artist or title and you can sort results by price or date of sale. Popsike has listings for record sales on eBay going back to 2003, though they note that their database is neither definitive nor exhaustive.

Discogs.com – This site offers records for sale along with photos, release dates, and other information regarding records of all kinds. It’s free to use as a reference; to buy or sell records at the site, you must create an account. One useful feature of the site is that all listings for titles that have previously been sold on the site list the average and highest prices for previous sales. This makes the site useful for finding the approximate value of a particular title.

Vinyl Records Value Conclusion

We hear from people all the time – “I have some records. What are they worth?” With most commodities, the answer is a fairly simple one. If you have an ounce of gold, it’s worth a certain amount of money. The same applies to a barrel of oil.

That’s not the case with records, however. Vinyl records value is determined by a number of factors, including condition, scarcity, the name of the artist, and a host of other things, both obvious and obscure.

Because the value of a particular record is tied to so many factors, it’s difficult to give a general answer as to its value without knowing all of the particulars about that particular pressing.

The quickest way to find out is to check with Popsike for a quick glance at recent sales. Keep in mind that these prices reflect retail sales, and not the amount of money that you’d receive if you’re selling to a store or a reseller. Keep in mind that the highest prices are paid for copies in near mint condition, which may or may not apply to the records you currently have in your possession.

Record collecting is a fascinating hobby, however, and the many factors that can go into determining vinyl records value are among the things that keep the hobby interesting to collectors.

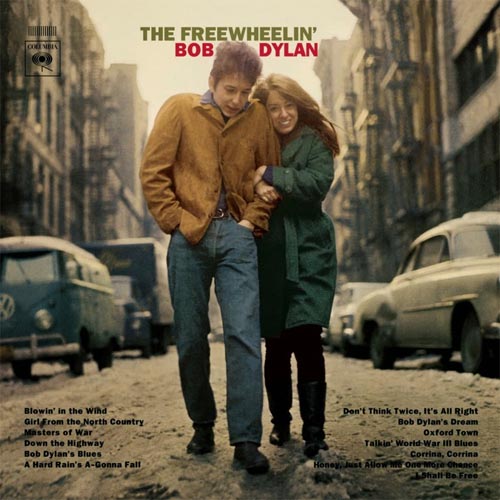

Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan with withdrawn tracks (1963) $35,000 – Bob Dylan’s first album, released in 1962, drew some critical notice but didn’t sell well enough to make the Billboard charts. His second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, on the other hand, drew attention and sold well enough to reach #22 on the American Billboard album chart.

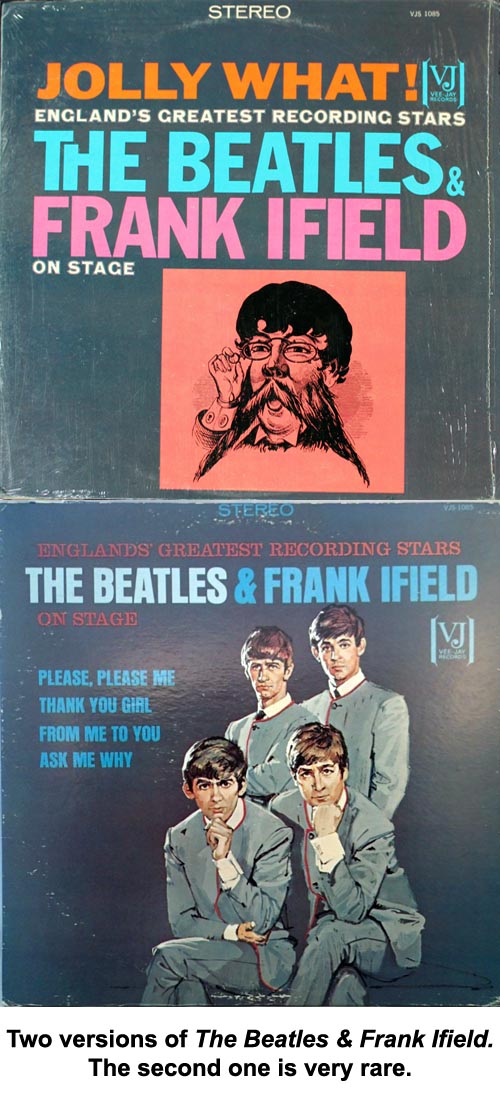

Bob Dylan – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan with withdrawn tracks (1963) $35,000 – Bob Dylan’s first album, released in 1962, drew some critical notice but didn’t sell well enough to make the Billboard charts. His second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, on the other hand, drew attention and sold well enough to reach #22 on the American Billboard album chart. The Beatles and Frank Ifield On Stage (1964) $30,000 – When the Beatles first started releasing records in Britain, their UK label, Parlophone, offered their contract to the label’s American counterpart, Capitol. Capitol declined the offer, as English acts hadn’t sold particularly well in the U.S. up to that point.

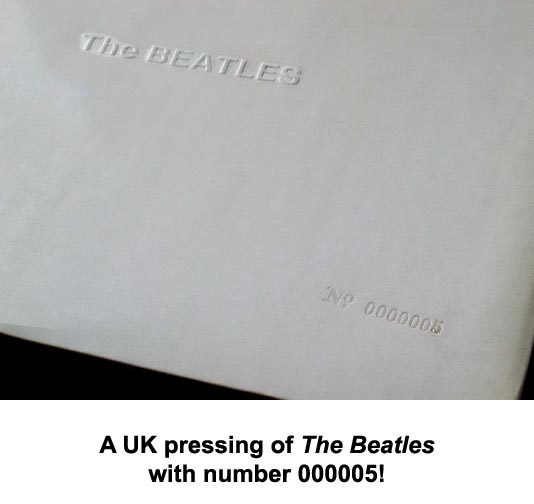

The Beatles and Frank Ifield On Stage (1964) $30,000 – When the Beatles first started releasing records in Britain, their UK label, Parlophone, offered their contract to the label’s American counterpart, Capitol. Capitol declined the offer, as English acts hadn’t sold particularly well in the U.S. up to that point. The Beatles – The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) low-numbered copies (1968) $10,000+ – After the 1967 LP Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album that had an unusually elaborate cover, the Beatles went minimalist on their 1968 follow-up. Titled simply The Beatles, the album had a cover that was all white, though the name of the band was embossed on the cover.

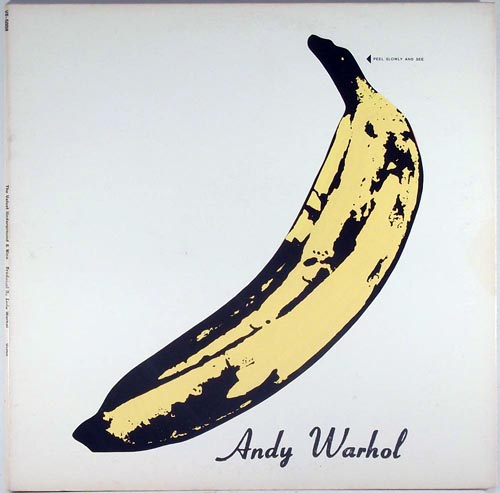

The Beatles – The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) low-numbered copies (1968) $10,000+ – After the 1967 LP Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album that had an unusually elaborate cover, the Beatles went minimalist on their 1968 follow-up. Titled simply The Beatles, the album had a cover that was all white, though the name of the band was embossed on the cover. The Velvet Underground & Nico – The Velvet Underground & Nico (1966) stereo pressing without the song “Sunday Morning” $22,000 – The 1966 debut by the Velvet Underground, the self-titled The Velvet Underground & Nico, sold poorly but remains one of the most influential albums of all time.

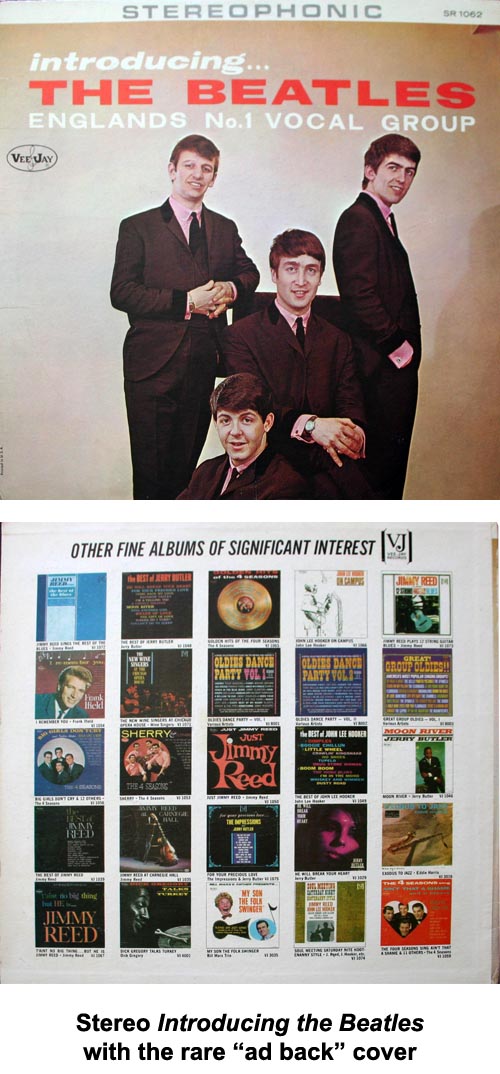

The Velvet Underground & Nico – The Velvet Underground & Nico (1966) stereo pressing without the song “Sunday Morning” $22,000 – The 1966 debut by the Velvet Underground, the self-titled The Velvet Underground & Nico, sold poorly but remains one of the most influential albums of all time. The Beatles – Introducing the Beatles stereo with “ad back” cover (1964) $15,000 – Yes, another Beatles album, and another album from the misfit label Vee Jay. Vee Jay had acquired the rights to an album’s worth of Beatles songs (released as Please Please Me in the UK) in 1963, but due to the poor sales of several singles, the label, which was strapped for cash, decided not to release the album.

The Beatles – Introducing the Beatles stereo with “ad back” cover (1964) $15,000 – Yes, another Beatles album, and another album from the misfit label Vee Jay. Vee Jay had acquired the rights to an album’s worth of Beatles songs (released as Please Please Me in the UK) in 1963, but due to the poor sales of several singles, the label, which was strapped for cash, decided not to release the album. The Beatles – Please Please Me UK stereo with black and gold label (1963) $21,000 – The Beatles first album, Please Please Me, was released in Britain nearly a year before its U.S. release as Introducing the Beatles. The album was initially released in March, 1963 in the UK on the Parlophone label, and first pressings were available only in mono.

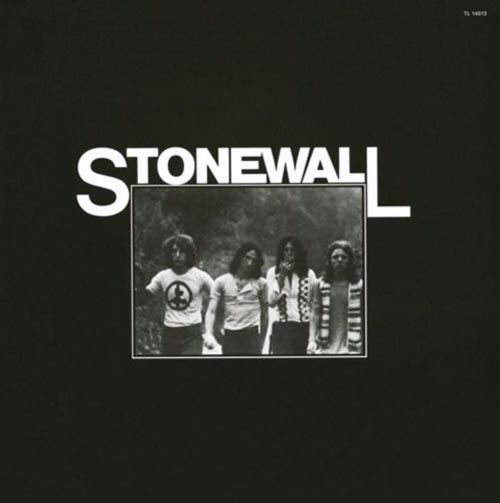

The Beatles – Please Please Me UK stereo with black and gold label (1963) $21,000 – The Beatles first album, Please Please Me, was released in Britain nearly a year before its U.S. release as Introducing the Beatles. The album was initially released in March, 1963 in the UK on the Parlophone label, and first pressings were available only in mono. Stonewall – Stonewall (1976) $14,000 – You may not have ever heard of a band called Stonewall, and that’s not surprising. They released only one album, the self-titled Stonewall in 1976, and it’s not even fair to suggest that that album was even properly released.

Stonewall – Stonewall (1976) $14,000 – You may not have ever heard of a band called Stonewall, and that’s not surprising. They released only one album, the self-titled Stonewall in 1976, and it’s not even fair to suggest that that album was even properly released. The Beatles – The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) UK export copies (1968) $10,000+ – Yes, the White Album appears on this list again. This time, it’s not the number on the cover that matters (though it might affect the price.) This particular version of the White Album is the version that Parlophone Records in Britain made especially for export.

The Beatles – The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) UK export copies (1968) $10,000+ – Yes, the White Album appears on this list again. This time, it’s not the number on the cover that matters (though it might affect the price.) This particular version of the White Album is the version that Parlophone Records in Britain made especially for export. Beatles – Yesterday and Today red Capitol “target” label (1971) – Yes, another pressing of Yesterday and Today by the Beatles qualifies as one of the most valuable vinyl records, but this one is not a Butcher Cover.

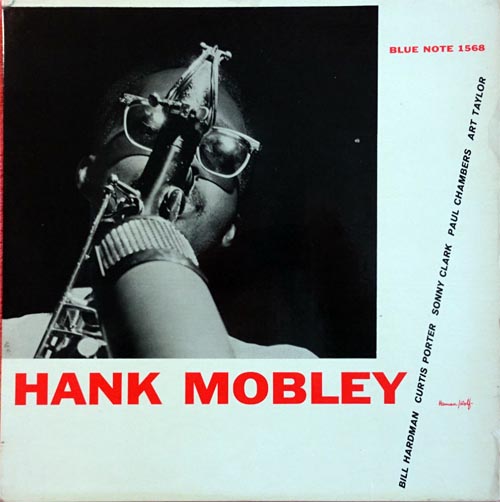

Beatles – Yesterday and Today red Capitol “target” label (1971) – Yes, another pressing of Yesterday and Today by the Beatles qualifies as one of the most valuable vinyl records, but this one is not a Butcher Cover. Hank Mobley – Hank Mobley Blue Note 1568 (1957) – $10,000 – Hank Mobley was a tenor saxophone player who had a long career, the early part of which was spent with Blue Note Records of New York City. Many of Blue Note’s releases from the 1950s have long been sought out by collectors, and first pressings of a number of their titles from the 1950s routinely sell for more than $1000.

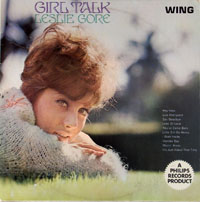

Hank Mobley – Hank Mobley Blue Note 1568 (1957) – $10,000 – Hank Mobley was a tenor saxophone player who had a long career, the early part of which was spent with Blue Note Records of New York City. Many of Blue Note’s releases from the 1950s have long been sought out by collectors, and first pressings of a number of their titles from the 1950s routinely sell for more than $1000. Lesley Gore albums – We have a number of rare and unusual Lesley Gore albums, including sealed original LPs, promotional LPs, radio shows, unusual foreign albums and even a few colored vinyl albums.

Lesley Gore albums – We have a number of rare and unusual Lesley Gore albums, including sealed original LPs, promotional LPs, radio shows, unusual foreign albums and even a few colored vinyl albums. Lesley Gore autographs – We have a few Lesley Gore autographs, as well, including photos, albums and compact discs.

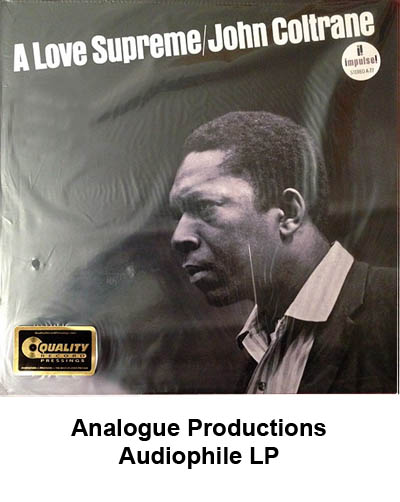

Lesley Gore autographs – We have a few Lesley Gore autographs, as well, including photos, albums and compact discs. The term “audiophile” has a number of meanings; one definition we found was, “hi-fi enthusiast: somebody who has an enthusiasm for sound reproduction, especially high-fidelity music recordings.” That’s probably a good overall assessment; it’s someone who has an appreciate for how music sounds.

The term “audiophile” has a number of meanings; one definition we found was, “hi-fi enthusiast: somebody who has an enthusiasm for sound reproduction, especially high-fidelity music recordings.” That’s probably a good overall assessment; it’s someone who has an appreciate for how music sounds.

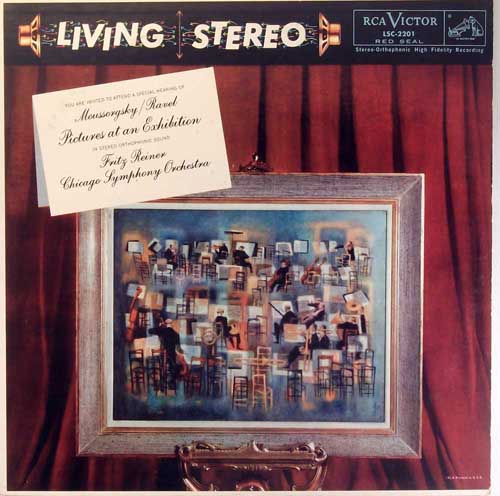

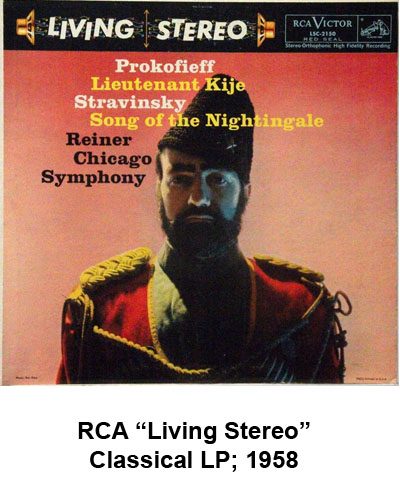

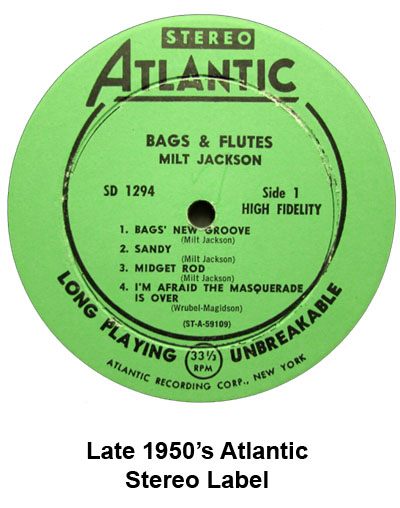

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few record companies, such as Columbia and Atlantic, spent a lot of time trying to make sure that their recordings sounded great and that their finished product was of a high quality. Their albums were well-recorded, with a sense of space and depth that truly immersed the listener in the experience.

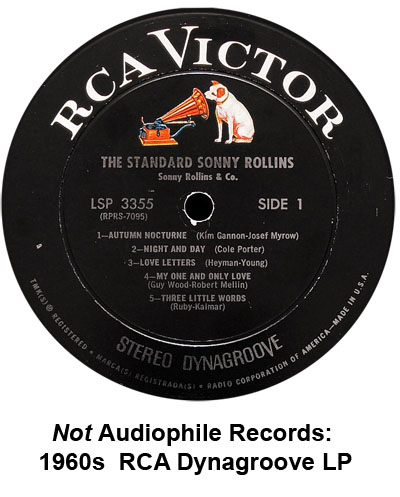

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few record companies, such as Columbia and Atlantic, spent a lot of time trying to make sure that their recordings sounded great and that their finished product was of a high quality. Their albums were well-recorded, with a sense of space and depth that truly immersed the listener in the experience. The price of stereo equipment began to drop as the 1960s wore on, and more people started buying stereo records. Their lower-priced equipment didn’t do as good a job of reproducing stereo sound, and RCA compensated for this beginning in 1963 when they introduced their “Dynagroove” process.

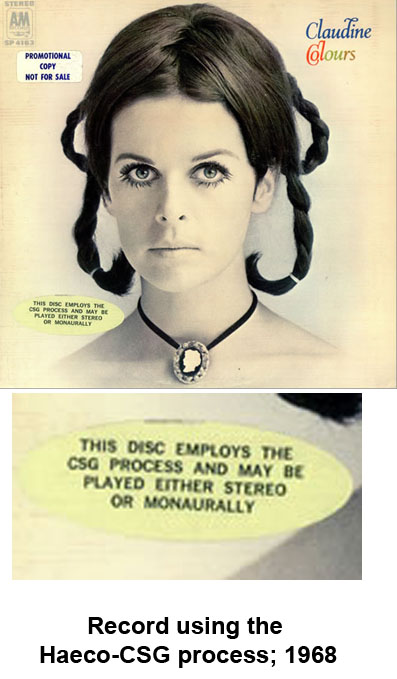

The price of stereo equipment began to drop as the 1960s wore on, and more people started buying stereo records. Their lower-priced equipment didn’t do as good a job of reproducing stereo sound, and RCA compensated for this beginning in 1963 when they introduced their “Dynagroove” process. While this was great for record companies, as it allowed them to dramatically reduce manufacturing costs, it was terrible for consumers who appreciated high-quality sound, as the phase-cancellation process used by CSG resulted in “tinny” sounding records with relatively little bass.

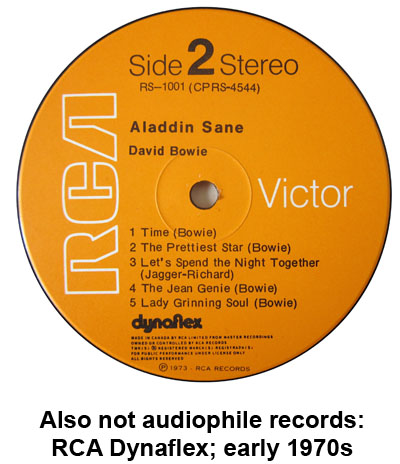

While this was great for record companies, as it allowed them to dramatically reduce manufacturing costs, it was terrible for consumers who appreciated high-quality sound, as the phase-cancellation process used by CSG resulted in “tinny” sounding records with relatively little bass. Perhaps the worst example of this were the records RCA pressed at this time. These were extraordinarily thin pressings were so thin that you could almost fold them in half.

Perhaps the worst example of this were the records RCA pressed at this time. These were extraordinarily thin pressings were so thin that you could almost fold them in half. As a side note, there was a small label in operation from the late 1940s through the 1970s that called itself “

As a side note, there was a small label in operation from the late 1940s through the 1970s that called itself “ In the early 1970s, a record mastering engineer named Doug Sax and a musician named Lincoln Mayorga discovered that many of their old 78 RPM singles sounded better than newer recordings. This led to the formation of one of the earliest companies to intentionally produce audiophile records – Sheffield Lab.

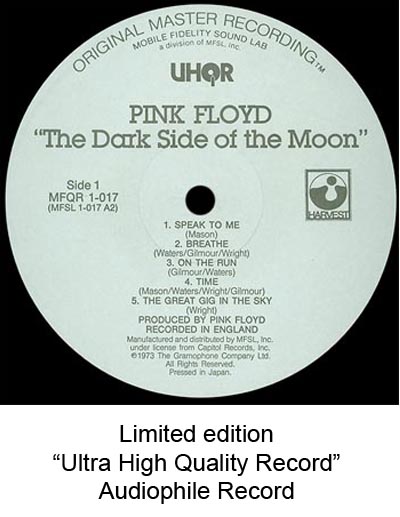

In the early 1970s, a record mastering engineer named Doug Sax and a musician named Lincoln Mayorga discovered that many of their old 78 RPM singles sounded better than newer recordings. This led to the formation of one of the earliest companies to intentionally produce audiophile records – Sheffield Lab. In the late 1970s, a company called Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, founded by Brad Miller, decided that it was time to produce audiophile records, meaning records that manufactured to sound good as the music on them, and records intended for people who actually care how their music sounds.

In the late 1970s, a company called Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, founded by Brad Miller, decided that it was time to produce audiophile records, meaning records that manufactured to sound good as the music on them, and records intended for people who actually care how their music sounds. The company also made the decision to use only new, high-quality, “virgin” vinyl, as opposed to the recycled vinyl that was then in use by nearly every major record company.

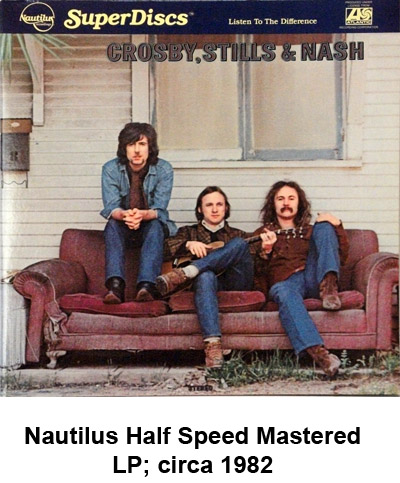

The company also made the decision to use only new, high-quality, “virgin” vinyl, as opposed to the recycled vinyl that was then in use by nearly every major record company. With the success of Mobile Fidelity, other companies soon joined the trend of releasing mass-produced audiophile records. Some of the early competitors were California-based Nautilus and Nashville’s Direct Disk Labs.

With the success of Mobile Fidelity, other companies soon joined the trend of releasing mass-produced audiophile records. Some of the early competitors were California-based Nautilus and Nashville’s Direct Disk Labs. Columbia’s audiophile records consisted of an odd mix of older, classic titles combined with then-new releases.

Columbia’s audiophile records consisted of an odd mix of older, classic titles combined with then-new releases. While all of this was going on, a few people quietly noticed that records imported from Japan tended to always sound better than their American counterparts.

While all of this was going on, a few people quietly noticed that records imported from Japan tended to always sound better than their American counterparts. After forcing records from the market in the early 1990s, the record companies found themselves with little product to sell after consumers balked at paying high prices for compact discs and resorted instead to illegally downloading low-quality mp3 files from the Internet.

After forcing records from the market in the early 1990s, the record companies found themselves with little product to sell after consumers balked at paying high prices for compact discs and resorted instead to illegally downloading low-quality mp3 files from the Internet.